Filip Hráček / text /

Benchmarking Flutter, Flame, Unity and Godot

For us game developers, it’s imperative to know the capabilities and limits of the technologies we use. For example, the original Super Mario Bros would hardly be a success if the game’s creators weren't intimately familiar with the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). Without that knowledge, they could have easily made a game behind its times, or — even worse — a game so complex that the console could simply not play it at all. At that point, no amount of whimsical art or inventive gameplay mechanics would have saved it.

I make games in Flutter. The one that’s been already out since 2021, Knights of San Francisco, is built in vanilla Flutter. That is to say, I didn't use any kind of game engine. (“It’s all widgets!”) The game that I’m currently working on, GIANT ROBOT GAME, is built with Flame. Flame is a Flutter package that makes video game development easier (while still retaining access to all of the functionalities of Flutter).

In both cases, it’s good to know how hard I can push. How far can these technologies take me? And, wouldn’t it be better to use one of the established game engines, such as Unity or Godot, instead?

There’s no benchmark that covers Flutter and Unity and Godot. Moreover, there’s no benchmark tuned for the games that people are likely to build in Flutter. So I decided to build one.

Here are the results but, frankly, they won’t make much sense until much later in this article.

Full disclosure: I’m a former member of the Flutter team and I still collaborate closely with them. As you’ll see, this benchmark is far from hyping Flutter. It’s meant as a way to find areas of improvement, not as a marketing effort. But I still feel it’s important to give this piece of context. I am biased.

Streetlight effect

You may have heard about the observational bias called the streetlight effect. This effect can be summarized by an old joke:

A policeman sees a drunk man searching for something under a streetlight and asks what the drunk has lost. He says he lost his keys and they both look under the streetlight together.

After a few minutes the policeman asks if he is sure he lost them here, and the drunk replies, no, and that he probably lost them in the park. The policeman asks why he is searching here, and the drunk replies, “this is where the light is”.

Benchmarks provide us with numbers that are easily compared and graphed. They’re the streetlight, and so they’re incredibly useful. But benchmarks can easily lead us astray when we don’t realize there are more things that aren’t (or even cannot) be lit by their light. (See also: McNamara fallacy.)

This is why context is crucial here. In the joke, the context is the fact that there’s a whole unlit park where the keys could be. So let’s see what the context is here, for my benchmark.

Scope

Gaming is a vast category nowadays. It contains both Wordle (a word puzzle game played mostly on mobile) and Star Citizen (a sci-fi simulation game for the latest Windows PCs).

Until proven otherwise, I think it’s safe to say that Flutter is not a good fit for most 3D games. Sure, you can render 3D in Flutter, and these capabilities are being developed further and further, but let’s just say that if I were CryEngine or Unreal Engine, I wouldn’t be worried just yet.

If you look at the most successful non-AAA games,* though, you’ll notice most of them aren’t in 3D. On mobile, there’s Candy Crush, Gardenscapes, Among Us, Monster Strike, Dead Cells, Cultist Simulator, Honeycomb. On desktops and consoles, there’s FTL, Undertale, Stardew Valley, Slay the Spire, Balatro. On the web, there’s Fallen London, A Dark Room, Agar.io, Kingdom of Loathing, Vampire Survivors.

*) AAA (read “Triple-A”) is a buzzword used to classify video games with high budgets. Think companies like EA, Ubisoft or Epic, typically, but the list goes on and on.

These are all 2D games. Most of them are built in minimalist 2D engines or frameworks. Others are built in 3D engines such as Unity but this is because 3D engines can pretend that the 3rd dimension doesn’t exist. (Sprites? How about rectangular textured polygons facing the camera!)

Flutter is really good at 2D. After all, apps are (mostly) 2D. And guess what, some successful 2D games are already built with Flutter.

But is Flutter fast enough, and efficient enough, to let you build the game of your dreams?

Games are different from apps. There’s more computation going on in the average game than in the average app. Moreover, games cannot afford having static screens. To create visual interest, something is always moving on a game screen. What if this “permanent animation” requirement erases Flutter’s optimization advantage. What if Flutter is actually a terribly ineffective technology for games?

My benchmark is targeted at 2D games. In terms of complexity, it tries to cover the range from something like Balatro (a card game with rich animations) to something like Vampire Survivors (real-time 2D action with many moving entities).

I’m especially interested in things that are important for indie games on mobile and the web. Startup time, efficiency, memory consumption.

Methodology

I built the exact same project using 4 different technologies:

- Flutter

- Meaning vanilla Flutter, without any additional engines, using widgets for everything, including game entities.

- Flame

- Meaning a Flutter app using Flame as the game’s framework.

- Godot

- Unity

(I used the latest stable versions for each technology as of August 2024: Flutter 3.24, Flame 1.18.0, Godot v4.2.2.stable.official and Unity 2022.3.39f1.)

I’d be happy to add more game engines to the list. If you have time and you’re interested in helping, please reach out!

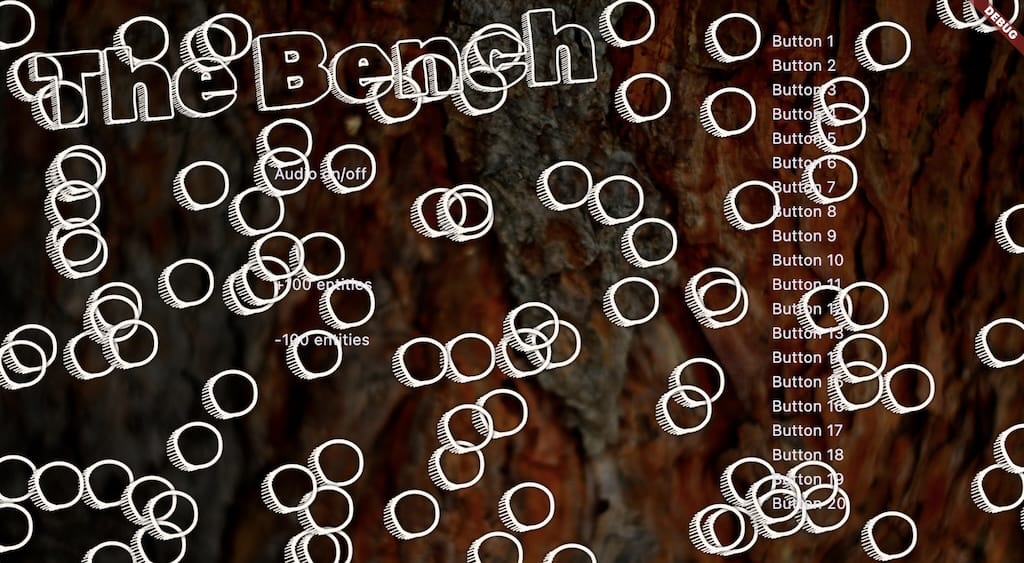

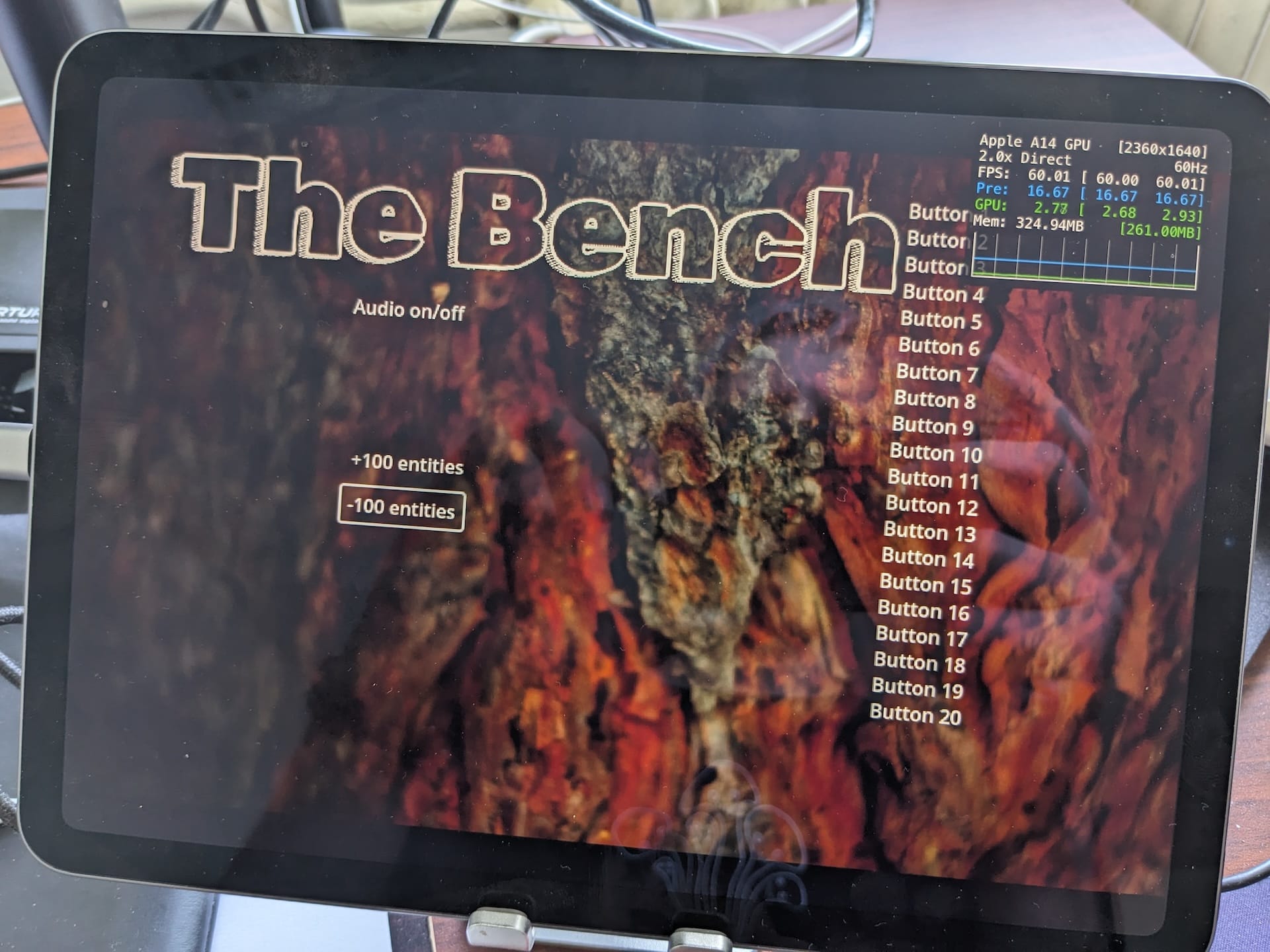

For clarity, I’ll call the project “The Bench” from now on. The Bench is not really a game, it just tries to simulate one. There’s nothing to play, but The Bench is designed so that it’s relatively easy to implement while exercising the same “muscles” that a 2D game would.

- High definition background artwork

- An element (large sprite) that’s moving every frame

- A variable amount of “wandering” entities that update every frame

- 23 UI elements

- One of them is audio on/off

- Two of them are for increasing and decreasing the number of entities

- The rest are 20 buttons that simply disappear when clicked

- Background music

The way the benchmark is implemented matters, of course. I could easily make one of the engines look bad by ignoring best practices. On the other hand, I could hand-optimize one of the versions of The Bench so well that it would make the engine look much better than it really is.

There’s an infamous example of how this affects benchmarks — The Computer Language Benchmarks Game. There’s more variance among programs in the same language than there is between languages. How the programs are written very much matters. Or, as the Benchmarks Game puts it, “If the fastest programs are hand-written vector instructions, does the host language matter?”

Therefore, my benchmark’s guiding principle was to always use general best practices of each engine but not to delve any deeper. If there’s a way to make the implementation faster but only the experts know it, then that optimization doesn’t get in. I realize this is vague. Who counts as an expert? Where is the line between general best practices and expert knowledge? But I feel this is the best I can do, really, without going full PhD thesis mode.

The code of every implementation of The Bench is open source so I rely on you, the reader, to correct me where I’m wrong. If there are things that most Unity programmers, for example, would do differently, I’m more than happy to fix my mistake, re-run the measurements, update this post and publish an erratum. But I tried very hard to use the canonical way of doing things for each game engine, and I stopped myself from using some of the Flutter knowledge that I know is beyond intermediate level.

In addition to how the programs are written, it also matters how they are compiled and for what target. In all cases (Flutter, Flame, Godot, Unity), the code is compiled in Release mode for the web and for iOS. It wouldn’t be too hard to compile for other targets (such as Android or macOS) but I’m not convinced the additional targets will give significantly different results and my time isn’t unlimited. Here, too, I’d welcome help from the community if anyone feels another target is worthwhile.

For the web, all engines are compiled to WASM (this is only optional for Flutter and Flame — the other engines always compile to WASM).

The devices I used for testing:

- For iOS, I used my iPad Air (4th Generation) testing device from 2020 running iPadOS 16.2.

- For the Web, I used the latest stable Chrome (Version 128.0.6613.86) on my daily-driver M1 MacBook Pro 13" from 2020 with 8 cores (4 performance, 4 efficiency), 16 GB of RAM, running macOS 14.4.1.

It’s important to note that I only measured each of the benchmarks presented below a couple of times. These are not robust statistics, so don’t get too hung up on minor differences. They might not exist in reality. That said, I’m fairly confident that all major differences are real.

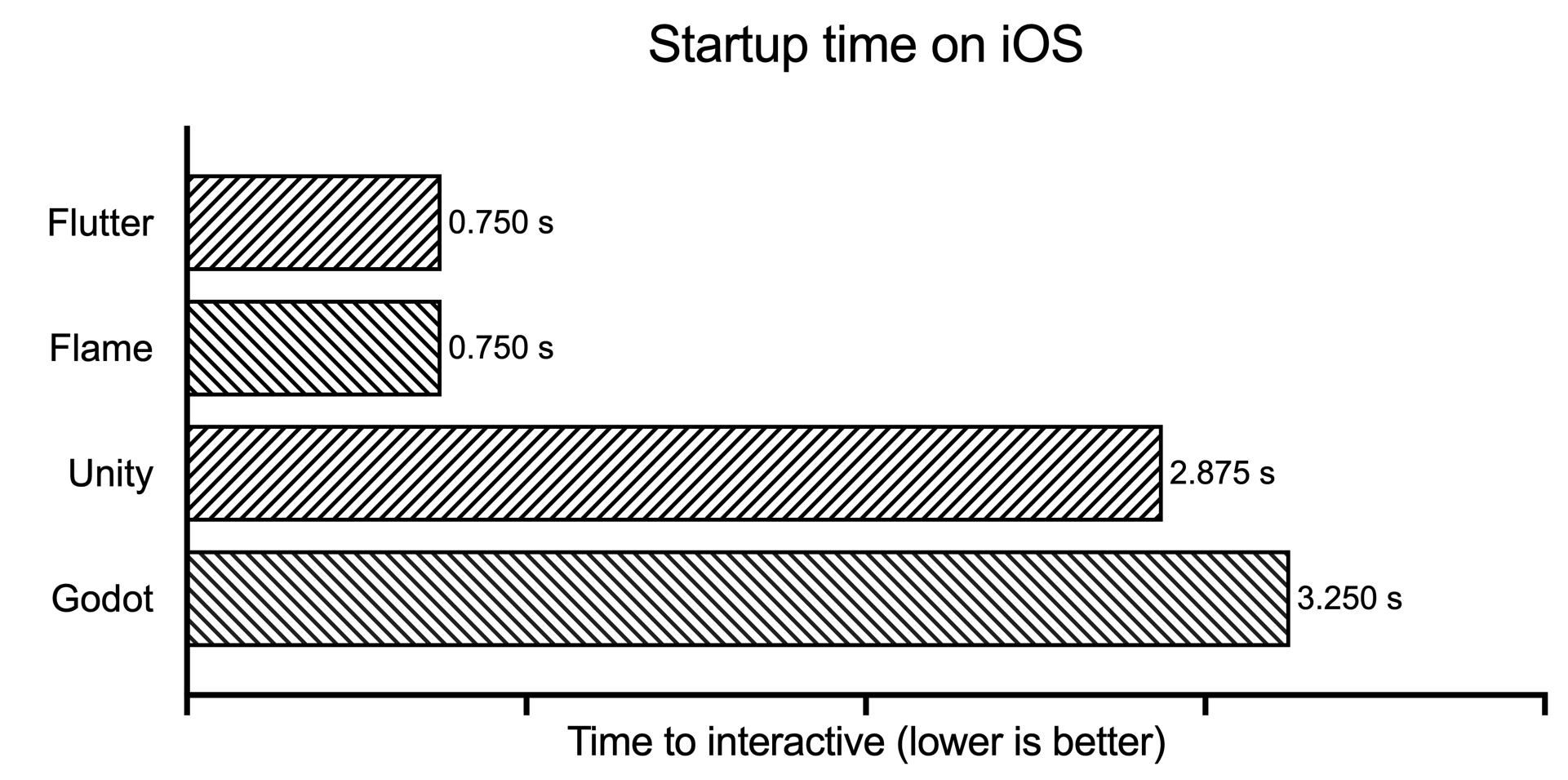

Startup time

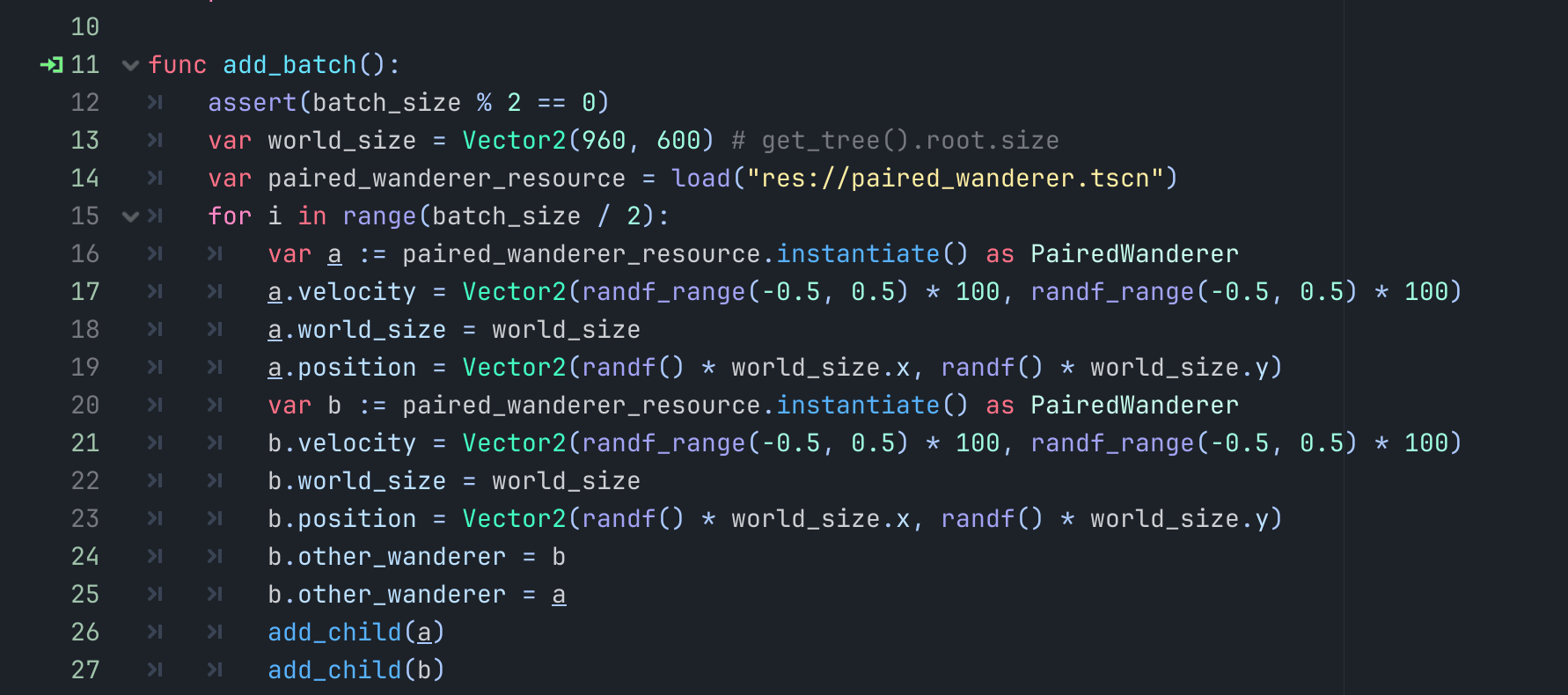

Big 3D titles such as Skyrim or Cyberpunk 2077 can take their time on the load screen because gamers play them in long, focused sessions. Indie games don’t have that luxury — especially not the ones on the casual side. Imagine games like Solitaire, Tetris or Wordle with 10-second loading screens! If web analytics is anything to go by, when it comes to user engagement, every second counts when it comes to startup times (in web parlance, longer page load times lead to higher bounce rates, among other things).

The first benchmark measures how long it takes for The Bench to show the first interactive frame. This includes loading the engine, running initialization, loading assets, initializing all the elements of the “idle” screen (without any wandering entities), and showing the first frame. On the web, this doesn’t involve playing the background music since browsers prevent audio playback until user interaction. But on other platforms, this limitation doesn’t exist, so I also count loading and playing the music file as part of startup on iOS.

Of course, some games will have additional loading screens during gameplay. But these loading times tend to be bound by the size of the game assets, not by the engine. Therefore, I focus on the initial game load here. The time to launch.

On the web, I used Chrome DevTools to measure the startup time. I used a localhost server and speed throttling in DevTools set to the “Fast 4G” setting. Chrome DevTools reports several metrics for load times; I looked at “Finish” (which is, in the case of The Bench, equivalent to Time-to-Interactive). I also recorded the amount of data that had to be downloaded (i.e. the compressed size of the project, since transfers on the web are gzipped or brotli'd). This data *didn't *include the background music file since, as mentioned above, web games can’t play anything until after the user interacts with the game in some way.

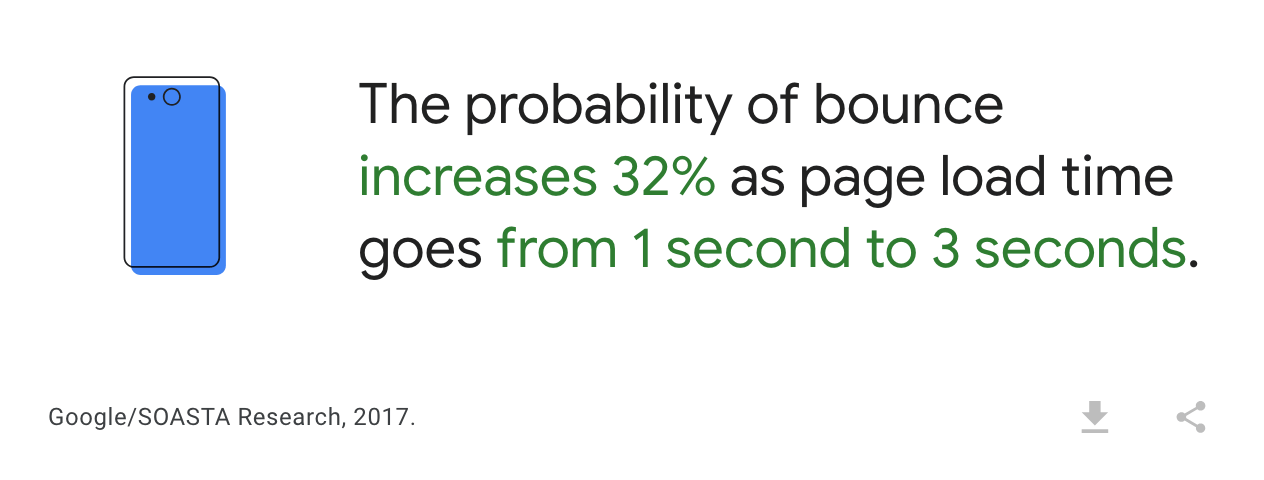

Unsurprisingly, the Flutter engine starts much faster than Unity, and (also unsurprisingly), the Flame engine is very close to Flutter (Flame is just Dart code, no additional libraries or assets are needed).

What’s surprising is how badly Godot fares. I tried my best to see if there’s a problem in my Godot project or the default export settings, but couldn’t find anything. That said, please take this result with a grain of salt, and do reach out if you know what’s going on there.

The vast majority of the load time on the web is taken by download.

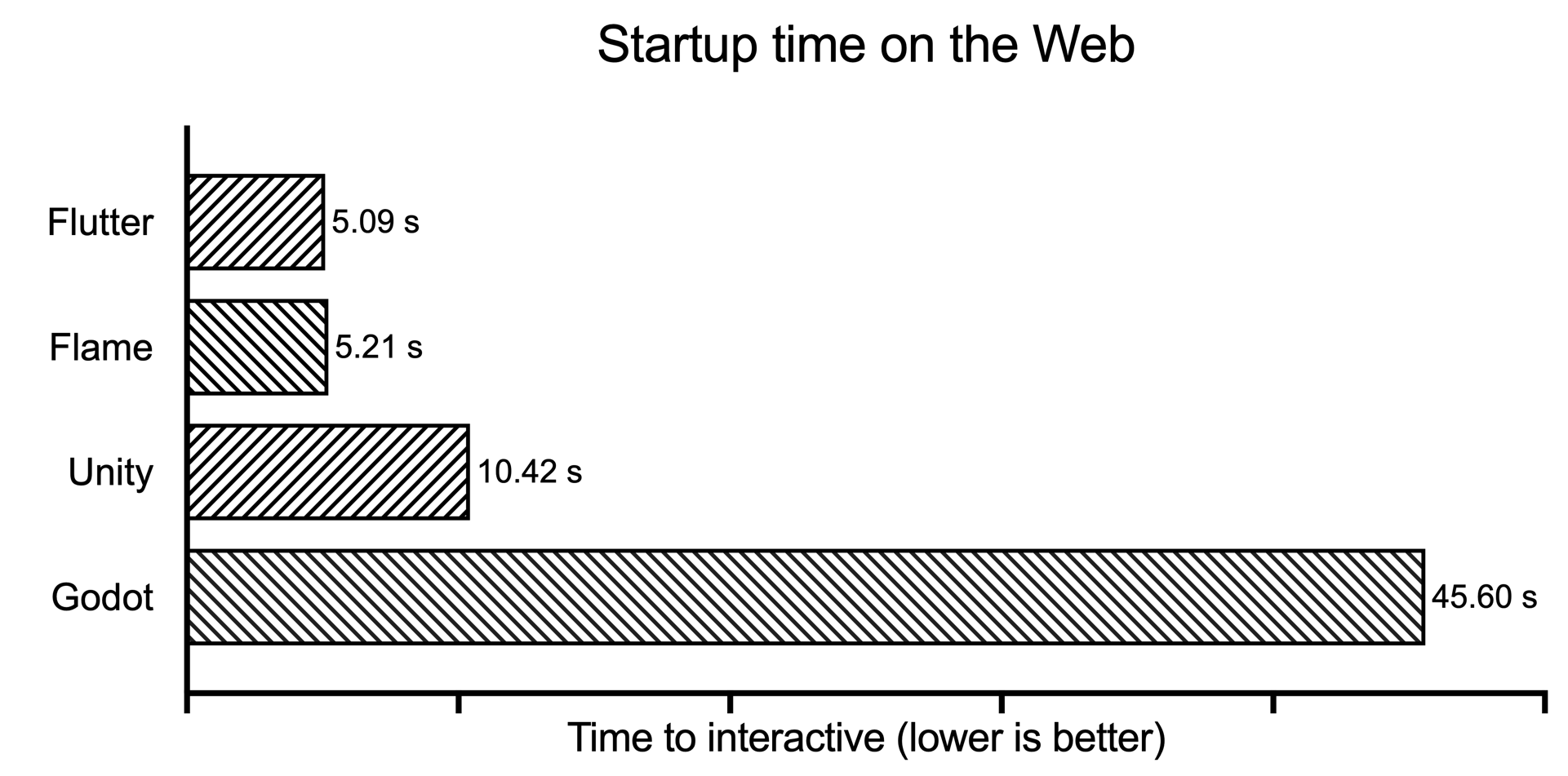

The sizes above include everything: from the HTML to the compiled (WASM) binaries to assets.

On the iPad, I measured the time between tapping the icon of the game, and seeing the first frame of the fully initialized game. When the first frame was partly obscured by some fading effect (as with Unity games, for example), I still counted it as the first frame. I used a slow motion camera to measure the time. Since mobile games are generally downloaded only once on install, and in one big chunk including all their assets, I didn't feel the need to measure the size of the download. In any real game, the size would be dominated by assets, not the engine.

Here, the startup advantage holds for Flutter and Flame. Unity and Godot are simply heavier engines.

There are a few things to note:

- On iOS, all apps start with a standard OS animation that “zooms” the tapped app icon. This alone takes close to 0.750 seconds, and I’m not sure how much of this time is given to the app for its initialization. I expect it’s close to zero. Therefore, when you see 0.750s startup time for Flutter, you could consider the startup time to be nearly instantaneous. But I thought discarding the startup animation would be unfair as it would ignore the end-user experience.

- The Godot export was configured with 0ms minimum splash screen. This means Godot only shows the Godot logo for as long as it needs for initialization, and then immediately goes to the game.

- As of today, Unity still requires showing the splash screen with the Unity logo. I’m not sure how long the minimum splash screen time is, but I assume it’s less than 2.875 seconds.

- Remember that The Bench is pretty light on initial assets and its initialization work is minimal. The Bench tries to be similar to small-ish indie games, after all. If the project was much larger, the initialization time would be dominated by assets more and more, and so the difference between Flutter and the traditional game engines would diminish.

Max entities

Most games need to track several interrelated entities at once. But there’s a big difference between something like Minesweeper, where the game only needs to update tiles after each player interaction, and something like Vampire Survivors, where hundreds of enemies need to get updated every frame.

The following benchmark will be less relevant to games like Minesweeper or Balatro or Slay the Spire, and more relevant to games like Vampire Survivors or Agar.io.

The idea is to see how many entities you can have in a real-time game at once. The hypothesis is that some game engines are better at tracking many interdependent game objects than others.

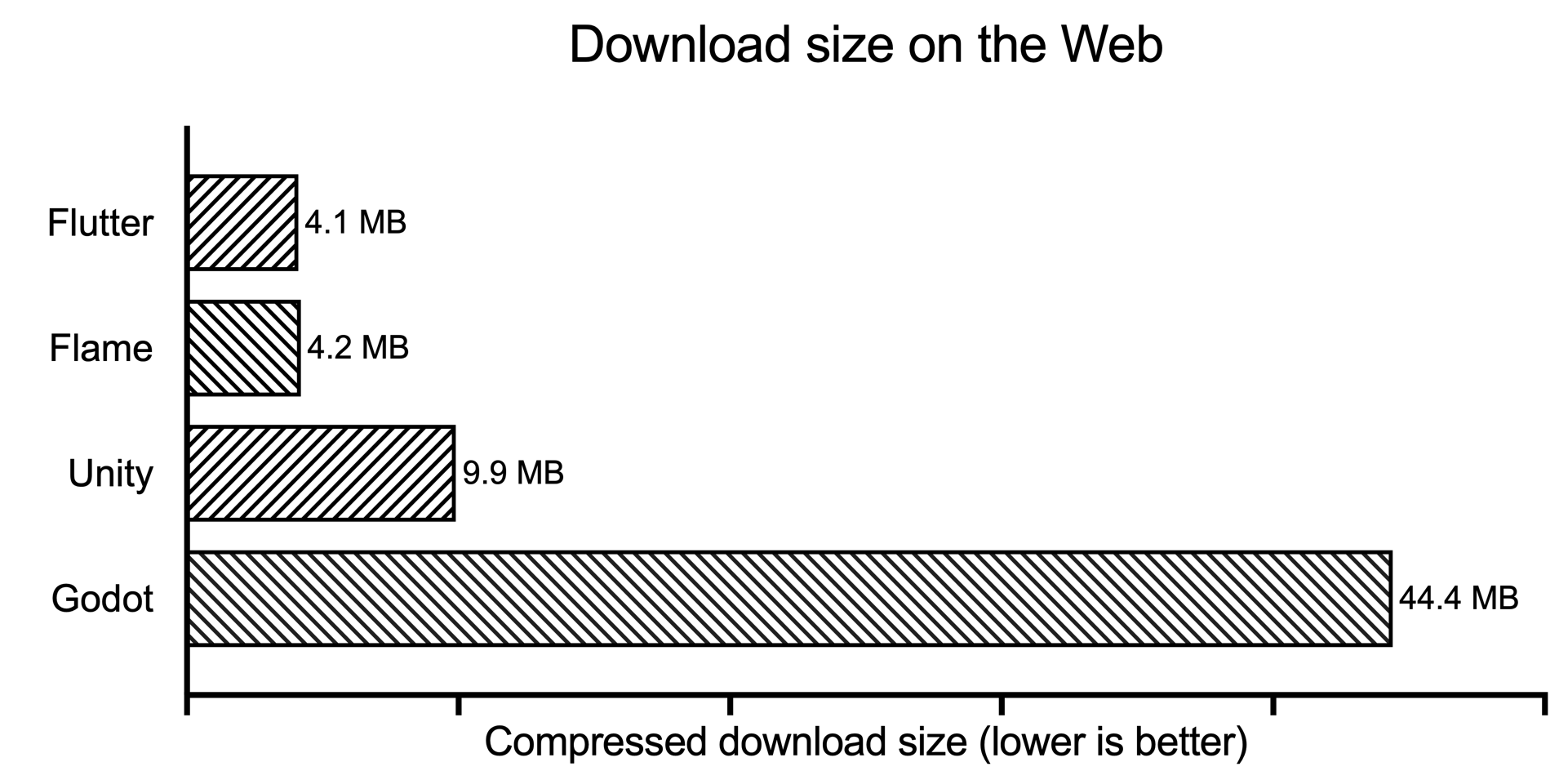

The Bench lets you add entities into the game world. These entities are relatively simple: they wander around the screen, bouncing off the edges. But each wanderer is paired with another random wanderer, and their velocity is interlinked. This is the simplest way (I could think of) of simulating the kind of entity interdependence that most games rely on.

There are benchmarks out there, such as Bunnymark, that measure particle system performance. This is not one of them. Particles tend to be short-lived, light and independent from each other. In contrast, game entities are generally long-lived, heavier, and they need to access the state of other game entities in order to decide what to do next. In some game engines, particles tend to be implemented completely differently from regular game objects (so that they can be optimized better). Don’t let the visual similarity to Bunnymark lead you to believe that this is a particle system benchmark. It’s not.

This benchmark could also be mistaken for a physics engine benchmark. While that would be an interesting excercise, too, comparing physics engines was explicitly not the goal. Most games aren’t physics based. For every single Angry Birds game (physics based), there are ten Flappy Birds (simplified hand-written physics) and a hundred Slay the Spires (no physics). So, again, don’t let the visuals fool you. The entities in The Bench are wandering around the screen, bouncing off screen edges, but they could just as easily stay put and rotate or update their Hit Points or something similar.

Here’s how the measurement went for iOS for each game engine:

- I compiled and built The Bench in Release mode for iOS.

- I ran the build on my testing iPad with the Metal Performance HUD turned on (here's how to do it via Xcode).

- I started adding entities in batches of 100, closely monitoring the Frames Per Second (FPS) reading.

- As soon as the average FPS went below 60.00, I removed the last batch, ensured that the FPS goes back to 60, and wrote down the number of entities on the screen.

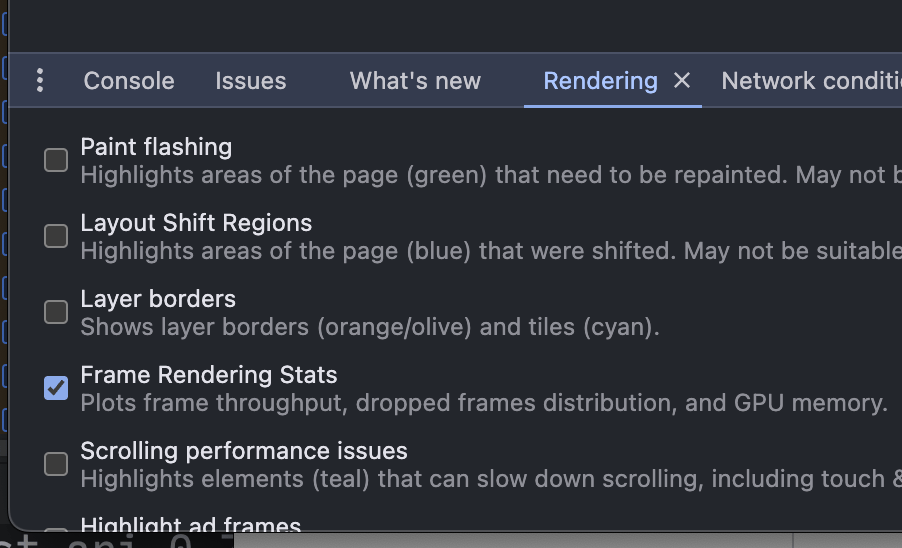

For the web, the method was analogous, except for using the Chrome DevTools Frame Rendering Stats option instead of Metal Performance HUD.

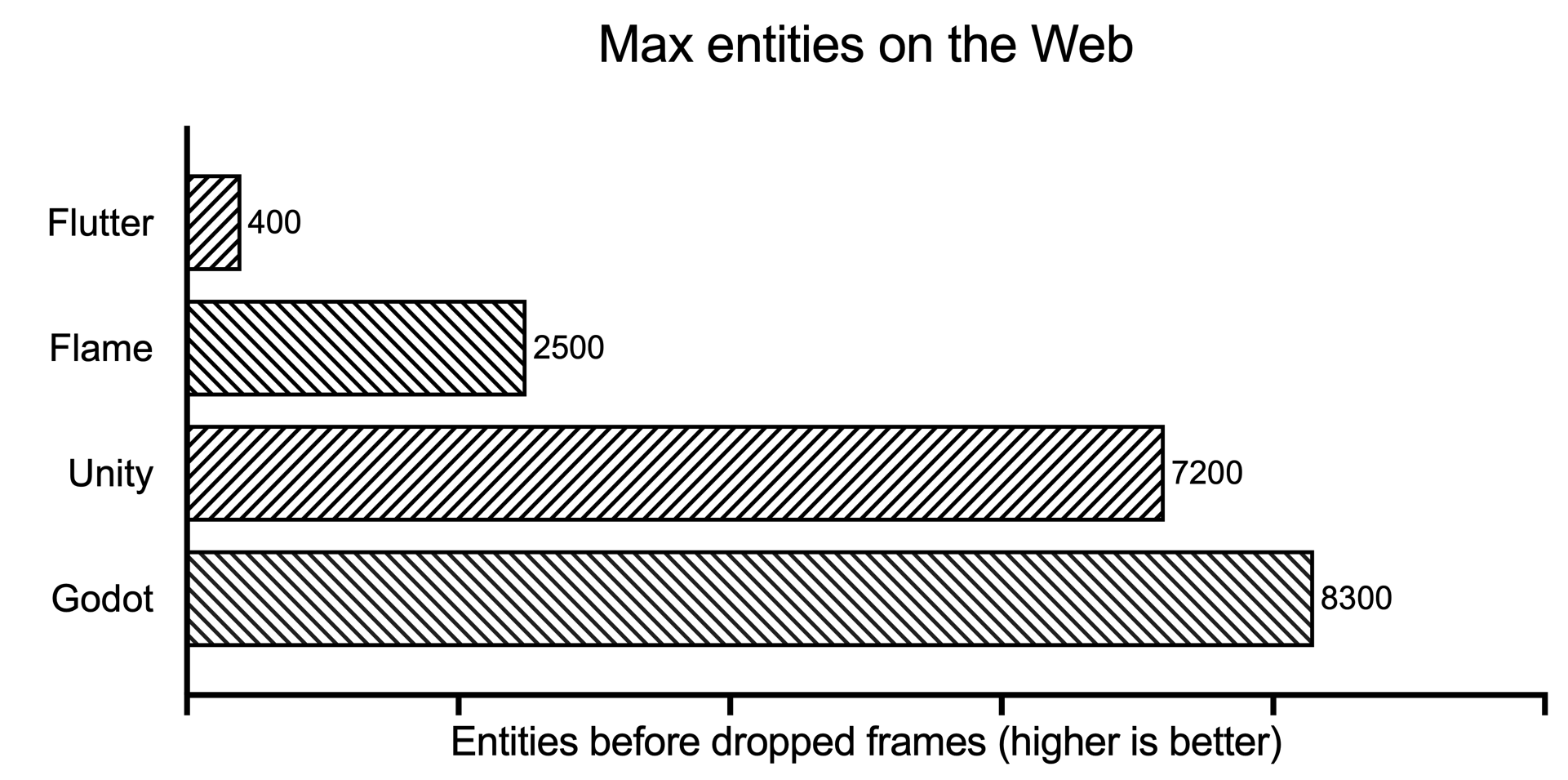

Here are the web results:

The fact that Unity and Godot are much better at tracking many game entities at once is not surprising. This is what they've been optimized to do. For Flame users, the good news is that their web game can still be quite busy — probably busier than most game genres require. That said, if you’re working on a bullet hell game or a Vampire Survivors-like, you might want to explore other options.

Flutter’s performance was a little strange. I got to 3600 entities without a dropped frame, but then I saw a few major frame drops so I kept coming down until the FPS stabilized again. This is how I got to the 400 number. I think it’s safe to say that vanilla Flutter is not the best game engine for busy action games. For the avoidance of doubt, I’d also like to remind you that the Flutter version of The Bench is all built purely using widgets. So the wandering objects on the screen are literally widgets in a Stack, rebuilt every single frame.

UPDATE: Jonah Williams from the Flutter team had a look at Flutter’s performance on The Bench when I shared the preview of this article with the team. Read on to learn the details.

A sidenote about SharedArrayBuffer. Modern browsers have technologies that unlock multi-threading performance on the web. This comes at a price, though. For security reasons, any page that enables these multi-threading capabilities must, at the same time, disable some other capabilities, including pretty basic things such as embedding. Both Unity and Godot require SharedArrayBuffer to be enabled for their web exports to work at all. This means that Unity and Godot games cannot run on servers that don’t have this special configuration. These incompatible servers include, well, most web servers on the internet. Many popular hosting platforms, such as GitHub Pages, don’t even have the option to enable SharedArrayBuffer. Thankfully, Flutter (and therefore Flame) doesn’t have this requirement. Flutter auto-detects whether it can use SharedArrayBuffer, and if so, it switches to multi-threaded mode. But it has no problem working in single-threaded mode on servers that don’t support the feature. You can read more about this here. In fact, I’m realizing (too late) that I neglected to enable SharedArrayBuffer for the localhost server when running the Flutter and Flame benchmarks. So we’re comparing single-threaded Flutter with multi-threaded Unity and Godot, even though multi-threaded Flutter is very much possible. It’s possible Flutter and Flame actually fare better on the web than what’s presented here.

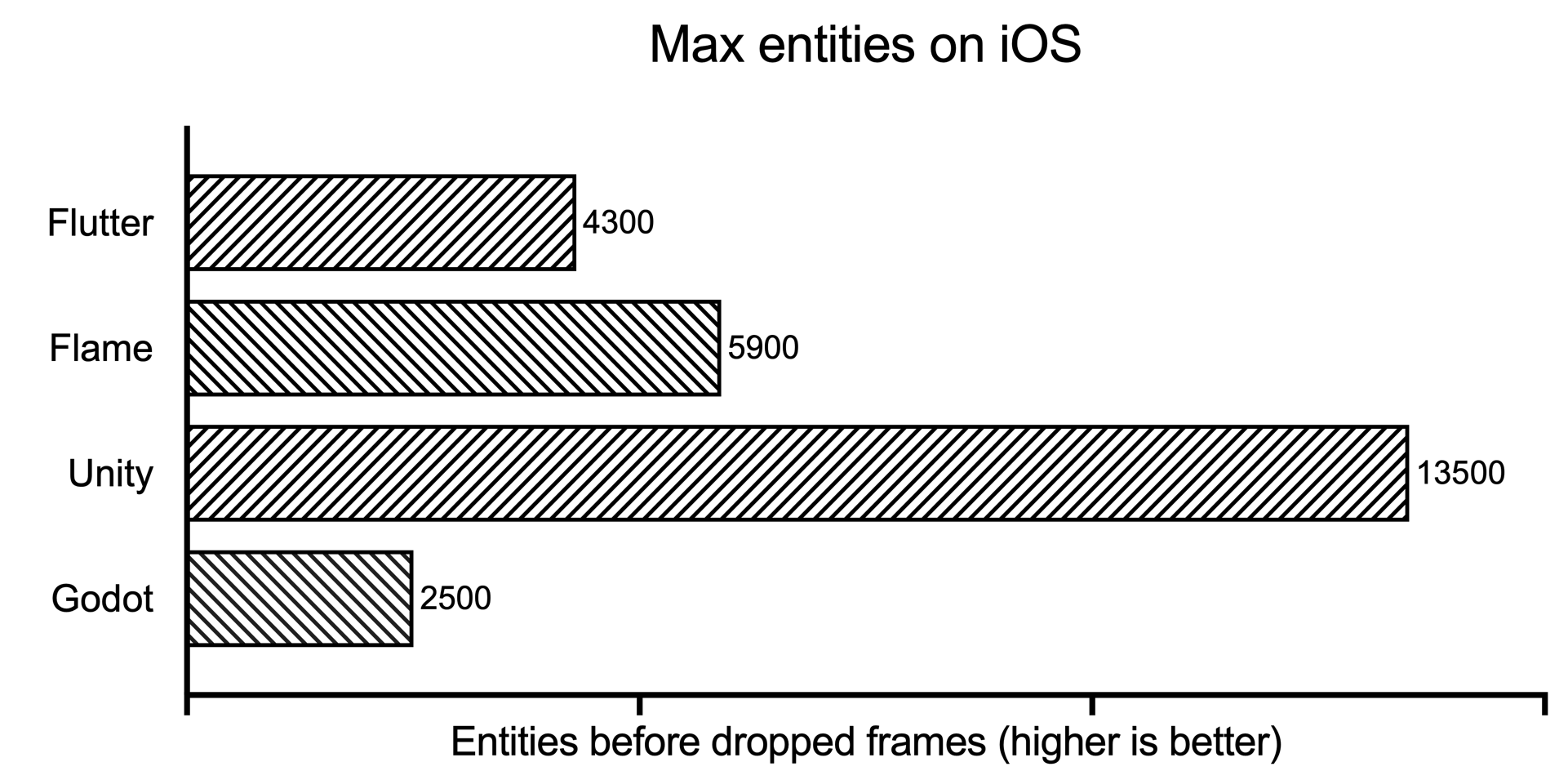

Here’s the Max entities situation on iOS:

First, I’d like to address Godot’s poor performance here. I simply have no idea what’s going on there, and I must assume it’s something I did wrong because I refuse to believe that Godot does worse when compiled for iOS than it does on the web. I tried two different rendering methods (metal and gl_compatibility) but saw similar results for both.

Second, as an aside, it was interesting to learn that Unity throttles iOS games to 30 FPS by default. This is a trade off I can completely understand since 30 FPS is probably more than enough for most mobile games, and it saves battery and reduces jank (it’s much harder to miss a 33ms frame than it is to miss a 16ms frame). That said, for the benefit of the benchmark, I forced Unity to render at 60 FPS (and I wasn’t disappointed by its performance).

Ignoring Godot’s outlier result, the conclusion on iOS is not that far from the one on the web. Unity has no problem tracking a huge number of game objects. Flame is significantly worse, but still — in my opinion — good enough for most game genres. Vanilla Flutter is worse still than Flame but also good enough for most game genres.

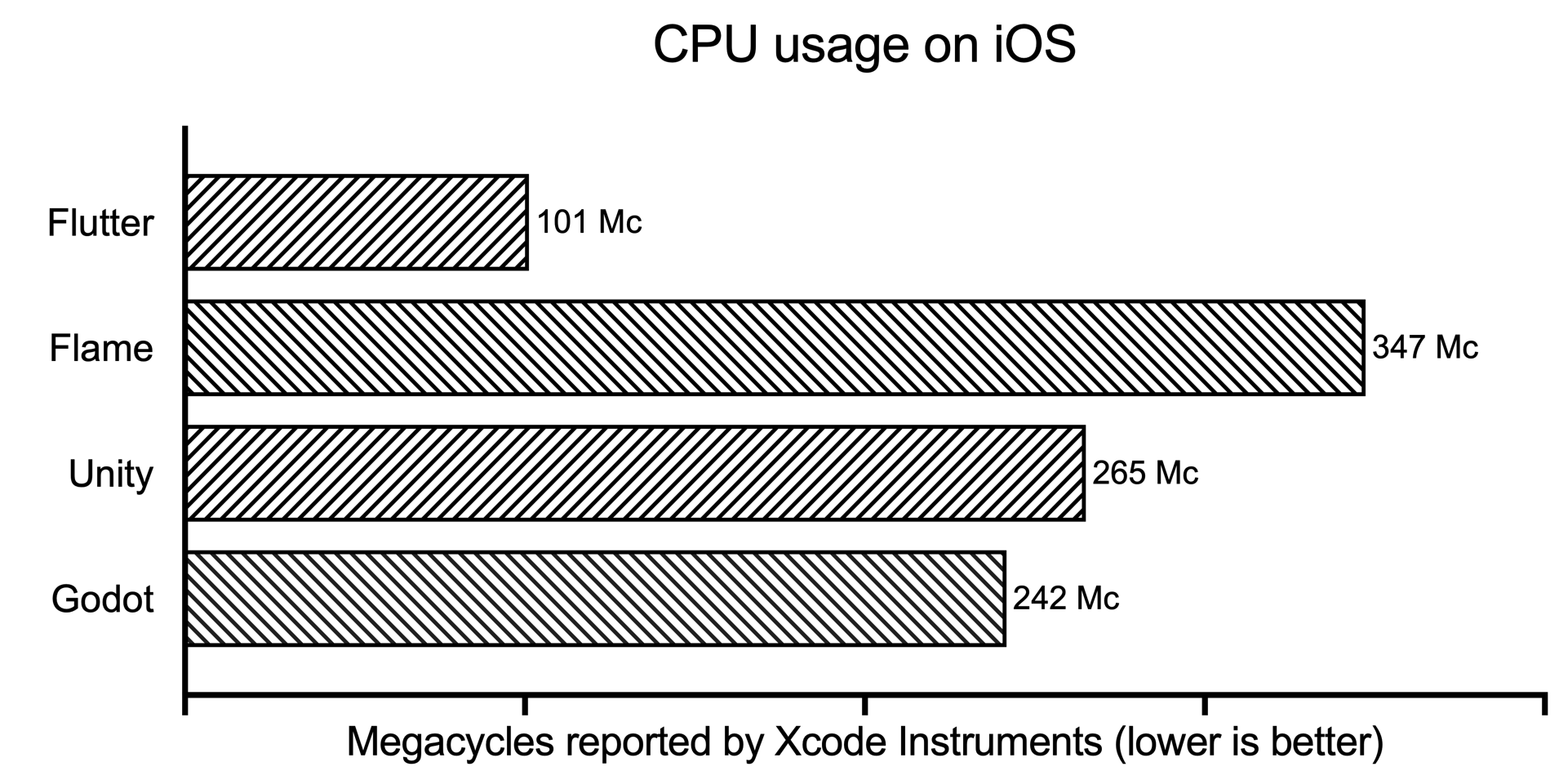

CPU usage

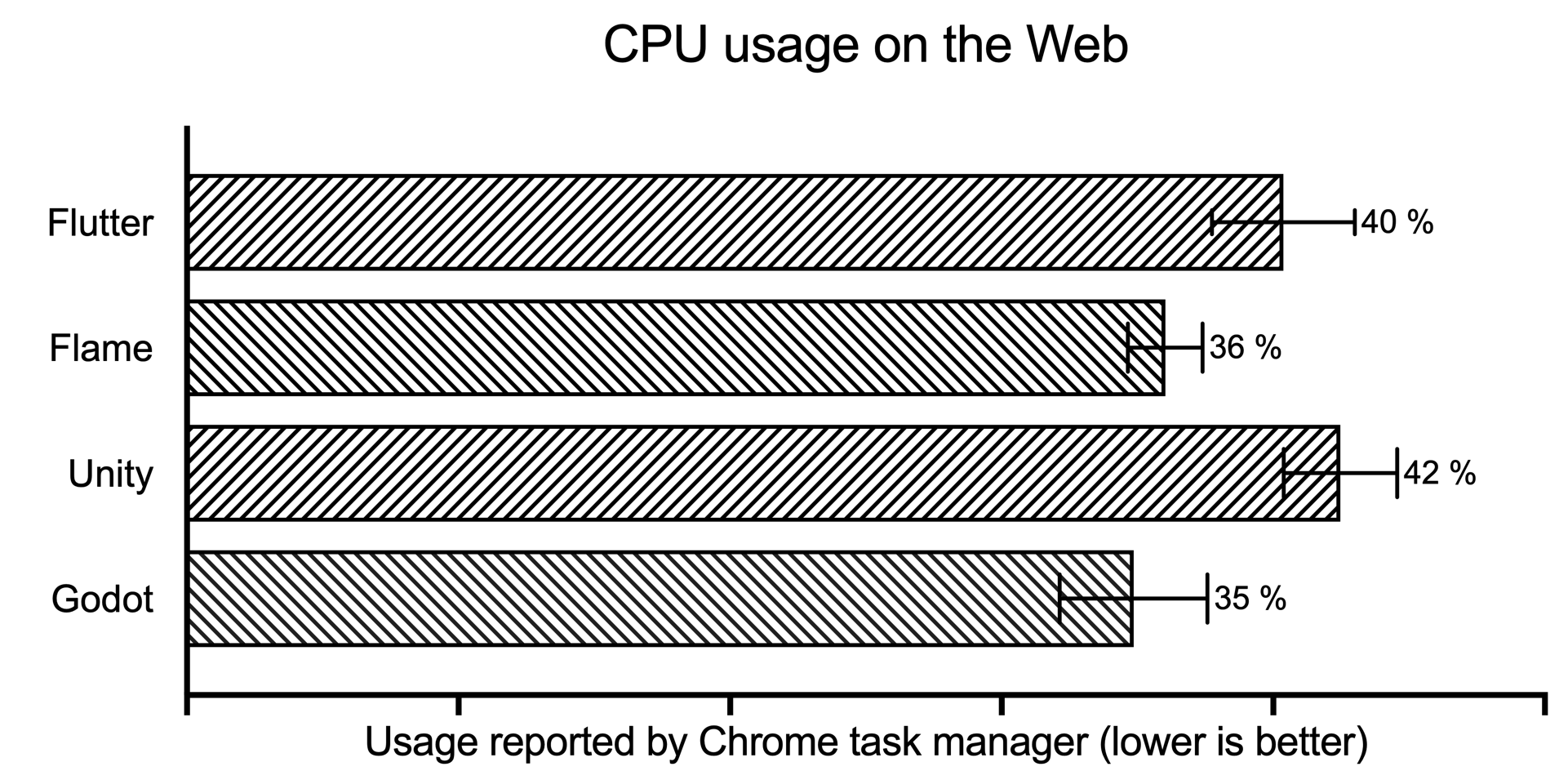

Like with startup time, here’s once again something that is nearly irrelevant for large gaming titles but quite important for the kinds of games people are likely to build in Flutter and Flame. People expect AAA games to utilize their computers and consoles to 100% — cooling fans and energy consumption on max. On the other hand, most 2D games are expected to be relatively gentle on CPU resources nowadays. People play on mobile or on their laptops, so battery drain is an issue. Unlike AAA titles, smaller games will also often need to coexist with other open applications without slowing the rest of the system to a crawl. And gamers will avoid games that make their laptop fans go into overdrive unless the game is a full headset-on experience.

In other words, the fact that a game engine can go brrrrrt is one thing, but it’s also important to see how CPU-efficient it can be when it’s not going as fast as it can.

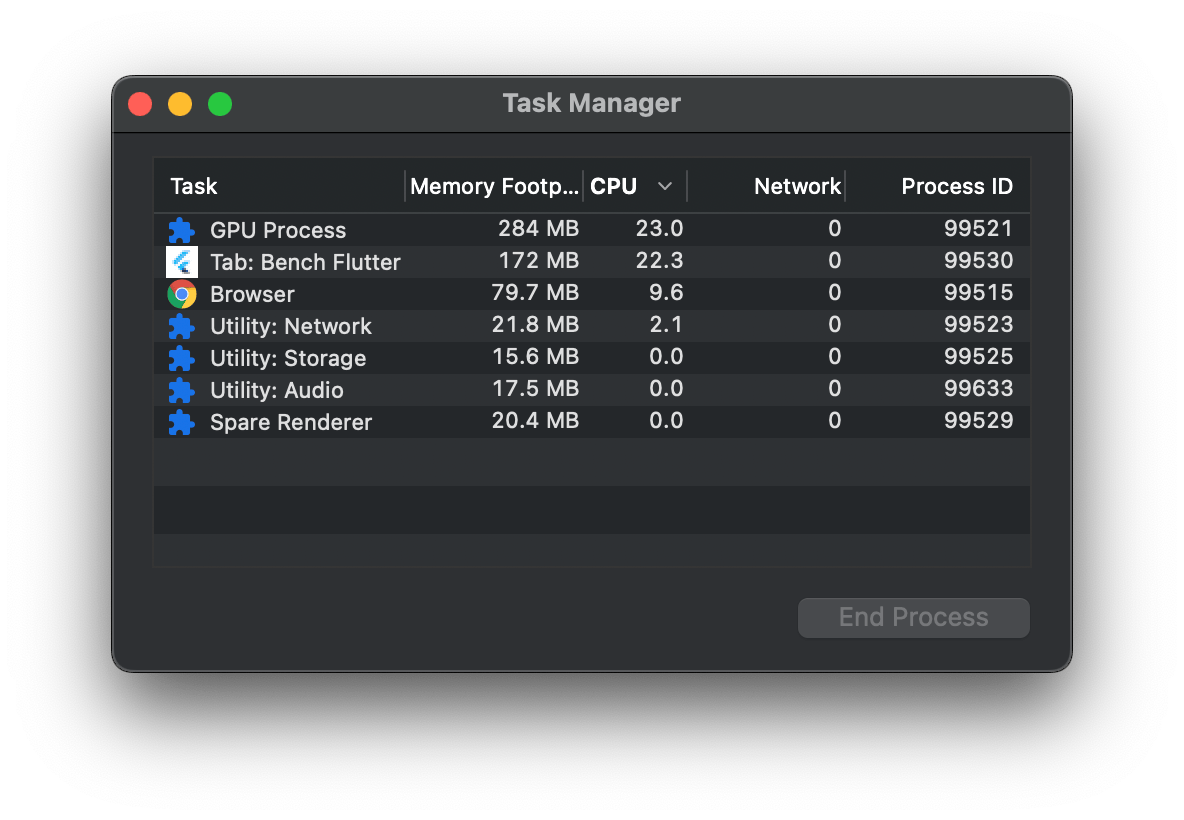

During the CPU usage benchmark, I have The Bench running with zero “wanderers” (see Max entities above), and I click on ten out of the twenty disappearing UI buttons. I then check the Chrome task manager to see how many percent of CPU the tab consumed during that time, and I add to it the percent needed for the “GPU Process” line.

If The Bench didn't have the permanent looping animation, and was instead as static as most apps are, I’d bet real money that Flutter would lead this benchmark by a significant margin. After all, Flutter only does work when the UI changes between frames.

But, as explained above, game screens aren’t ever static.

As you can see, on the web, the engines are close to each other at around 35-40% of combined CPU time.

On iOS, the story is a bit more complicated. Here, I have access to a more precise measurement thanks to Xcode Instruments. I can measure the total number of CPU cycles that an app needed during a window of time. The graph above shows totals for a 5 second window during which I interact with the game’s UI as described previously.

As you can see, on iOS, vanilla Flutter can be a lot more efficient than the other engines. This is the case despite the constant movement — I’m guessing this is because Flutter can be smart about what to update and re-render while the approach of traditional game engines is to simply re-render everything every frame. I’m not sure if this advantage on iOS generalizes to all other non-web targets, or all other Impeller targets, or if it’s just something specific to iOS.

To give some context to the numbers, here are 5 second CPU cycle measurements for other apps on the same device:

- Settings (OS preferences app)

- 702 Mc when scrolling up and down the “General” tab

- 0 Mc when the app is left alone

- 130 Mc when there’s a single interaction — switching from one tab to another — during the 5 second window

- Procreate (a drawing app)

- 1420 Mc when continuously drawing a line

- 94 Kc when the app is left alone

- YouTube, GarageBand, iMovie, Numbers, Keynote

- “Permission to debug com.google.ios.youtube was denied.”

- “Permission to debug com.apple.mobilegarageband was denied.”

- etc.

UPDATE: Jonah Williams from the Flutter team had a look at Flutter’s performance on The Bench when I shared the preview of this article with the team. Read on to learn the details.

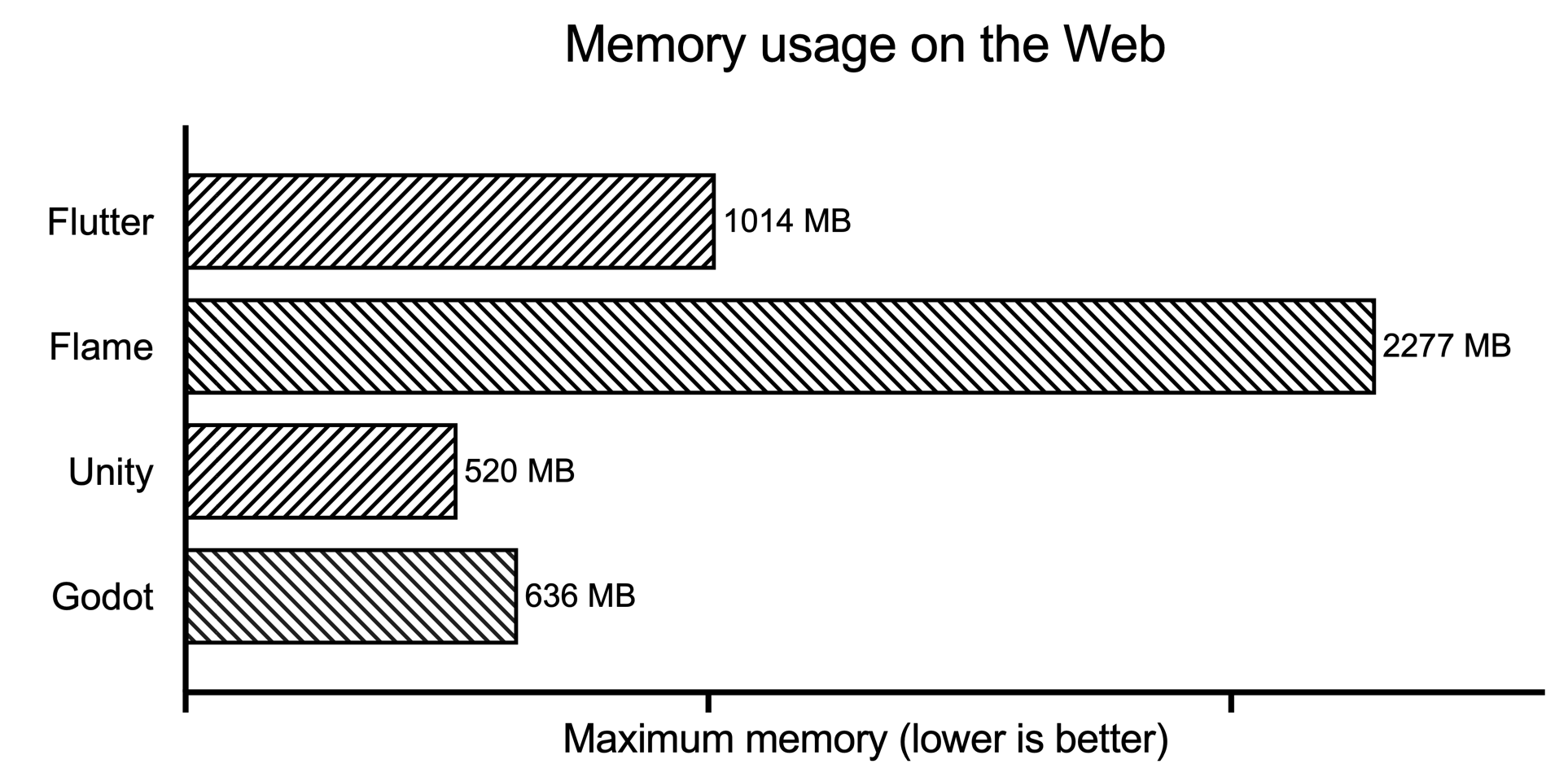

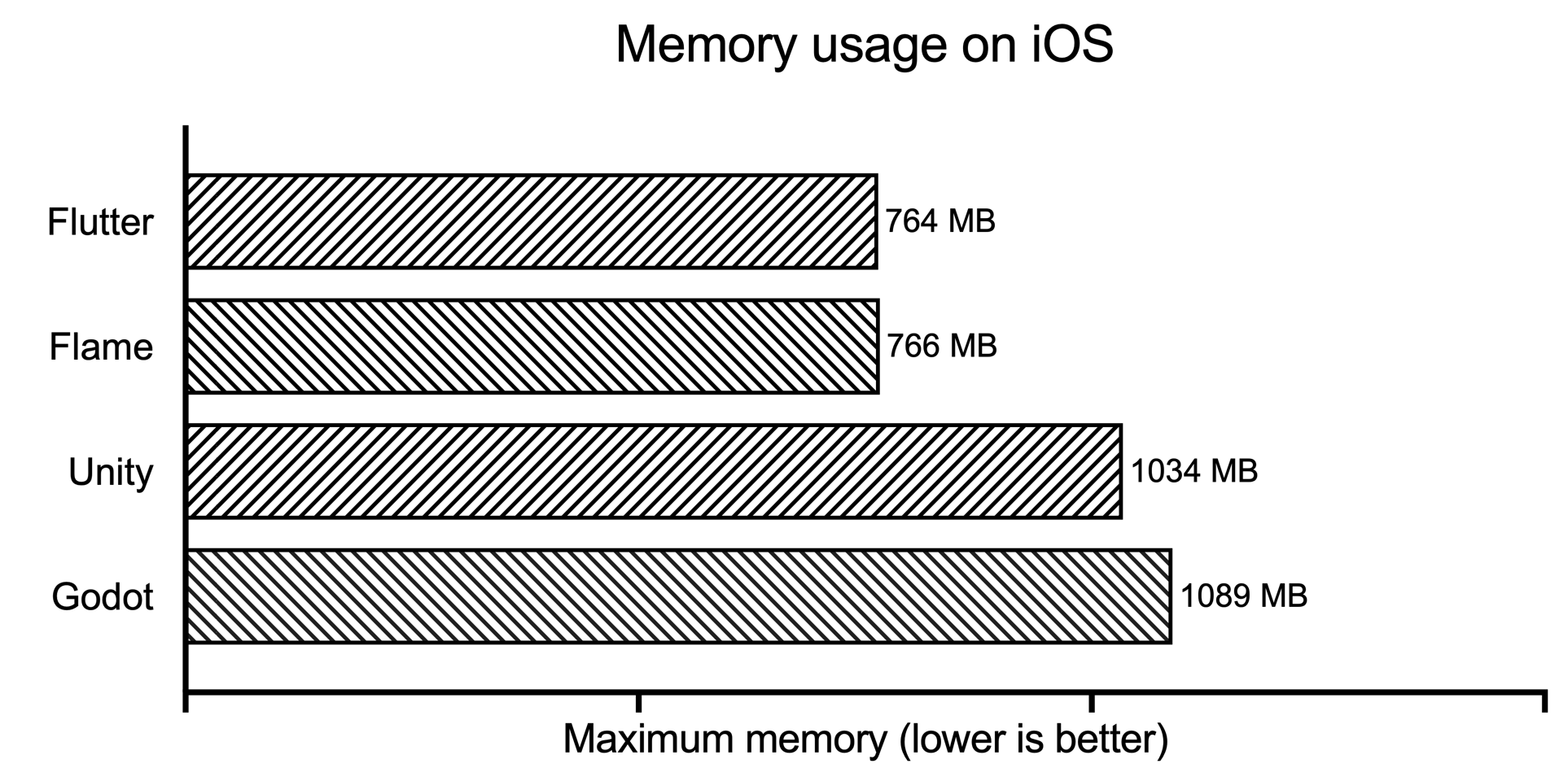

Memory usage

Apart from CPU usage, game developers should also care about how memory hungry their game engines are. Although your game will probably never hit an “out of memory” error these days (physical RAM is augmented with virtual memory on modern systems), too much memory consumption is still bad news. It will make garbage collection jank more likely and it’ll slow down the whole system when virtual memory is used instead of physical memory. Moreover, browsers can decide to “crash” the whole tab if they evaluate the tab’s RAM allocation trend as a memory leak.

For this benchmark, I ran The Bench with 1000 entities for 60 seconds, and measured the memory footprint of the game. I then picked the maximum during the 60-second window. On the web, I summed the game’s tab memory with the “GPU Process” memory reported by Chrome Task Manager.

As you can see, the Flutter and Flame versions of The Bench consume a lot more memory on the web than the Unity and Godot versions. In fact, the allocated memory size rose even further after the 60 seconds. It’s not a memory leak — the memory gets reclaimed eventually — but the engine isn’t aggressive enough in freeing memory on the web.

UPDATE: I reported this as an issue on the Flutter bug tracker. Between then and the publishing of this article, the issue has been largely addressed. Read on for details.

Unity and Godot are on similar footing, with Godot claiming a bit more memory but also having a lot more consistent consumption (while Unity’s RAM allocation fluctuated, Godot stayed at the same level for dozens of seconds at a time).

On iOS, I used Xcode Instruments' Game Memory tool to track the memory space of The Bench over one minute. I summed the Dirty Size, Swapped Size and Resident Size and found the maximum during the measured 60 seconds.

Flutter and Flame keep a lower resident memory footprint than Unity and Godot. To be clear, Flutter and Flame allocate (and then immediately free) a lot more memory than both Unity and Godot. I thought this would translate to a larger CPU footprint but, looking back at the CPU usage section, apparently it does not? If anyone has more context on this, I’m happy to update the article.

Updates from the Flutter team

Before I go on to the conclusion, let me share some good news.

First off, the memory issue on the web is largely addressed and there’s a lot more work being done on memory consumption on the web. My thanks go to Yegor Jbanov and Slava Egorov for looking into the bug I filed. I did not have time to rerun the Memory usage benchmark yet but I trust the results will be significantly better.

When I shared the preview of this article with the Flutter team, Jonah Williams (Staff SWE at Flutter) had a closer look. At first, he was suspicious about Flutter’s relatively good result on the CPU usage benchmark on iOS. “Depending on how the benchmark is running, Flutter could be hitting some very efficient usage of dirty region management - and skipping a lot of work,” he wrote. He went ahead and thoroughly profiled The Bench on iOS.

You can read his investigation doc here. I highly recommend reading it if you care about game performance in Flutter but I also want to offer a summary:

- The app is not hitting any dirty region management jackpot, as Jonah suspected at first. So the result is legit.

- A small but significant amount of the UI thread work is due to a newly discovered inefficiency around fonts on the engine side (Flutter doesn’t cache something that it should). This is a Flutter SDK bug to be fixed — the second one found because of this article. You can buy me a drink if the fixing of this bug makes your app or game more performant just by upgrading to the newest SDK version.

- Another significant amount of UI thread work is used by

RenderImage. Jonah recommends that, if you’re going to use many images in a game, that you don’t use a bunch ofImage()widgets and instead useCustomPainter()withdrawAtlas(). (This is what Flame is doing, by the way. Read on to learn how to do this in Flutter.) - Additionally, some work on the UI thread is taken up by

Semanticswidgets (which Flutter uses for accessibility features, such as screen readers). It depends on the game whether or not you want to pay this price. For some games, accessibility is a completely natural thing to want. Think card games or many deck-builder games. For these games, Flutter makes it easy (and sometimes automatic) to make them accessible. For other games, though, accessibility through screen readers is not practical (think Tetris or Vampire Survivors or, well, most games I can think of), and for those, you might consider actively disabling accessibility withExcludeSemantics().

I want to reiterate that, in real life, the answer to most performance questions is the disappointing “it depends”. For example, I can imagine many games that are very happy with the current performance of Flutter, even with the overhead of Image() widgets and Semantics().

Games that need a little bit of juice can still happily use vanilla Flutter if they do things like avoiding too many Image() widgets. Jonah provides a diff that makes that change to The Bench. It doesn’t add too many lines of code, and yet it makes the wanderers a lot more efficient — by putting them all into one CustomPainter(). I don’t add this optimization into the Flutter vanilla version of the benchmark because that would be against my methodology (see the section about expert knowledge above). That said, it’s important to understand that Flutter does give you ways to improve sprite rendering performance. You don’t need to implement everything as a widget, of course, and if you’re building a sprite-heavy game, you probably shouldn’t.

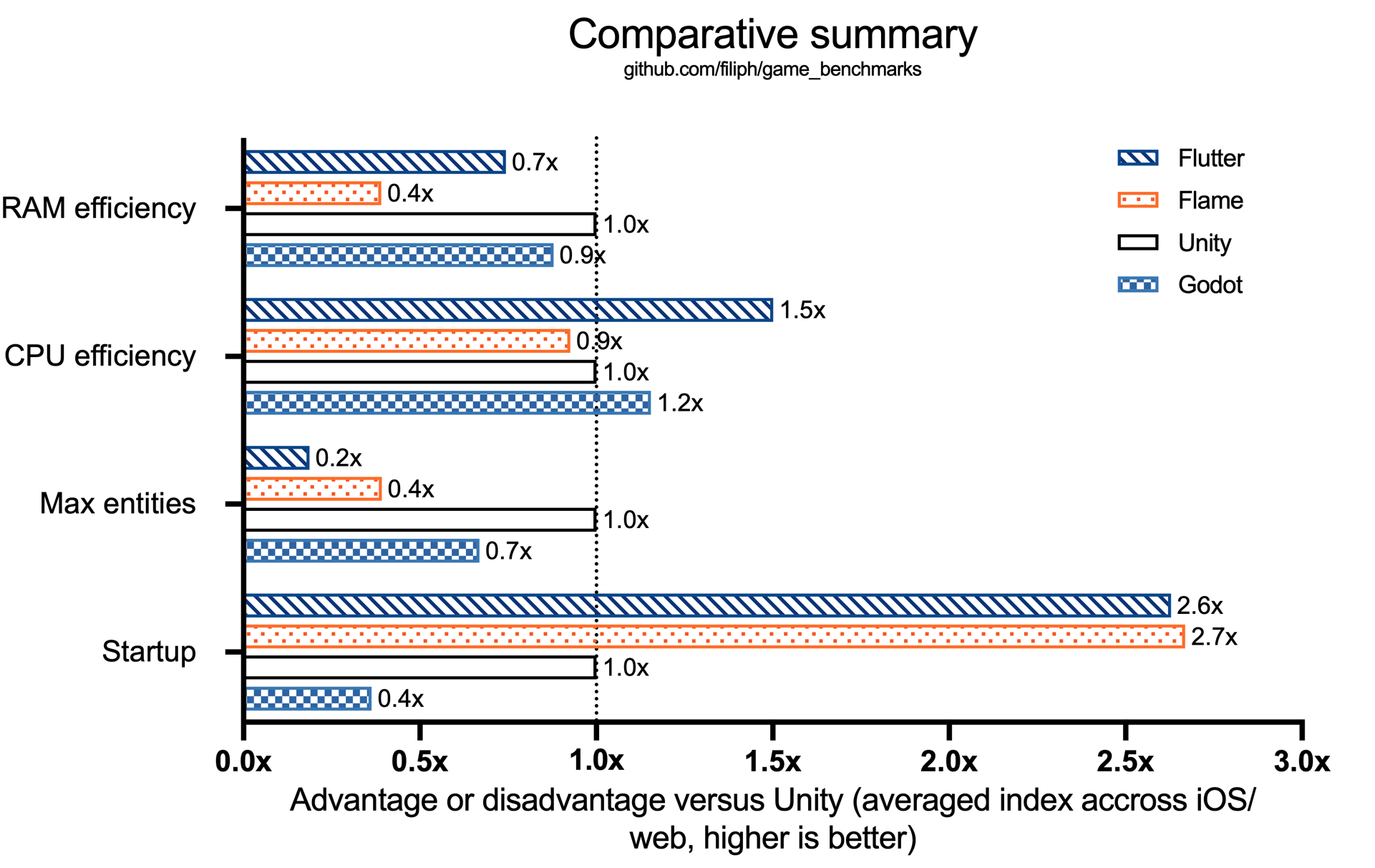

Conclusion

I could just stop right here and leave you to make your own conclusions. But I feel the length of the article warrants at least a summary.

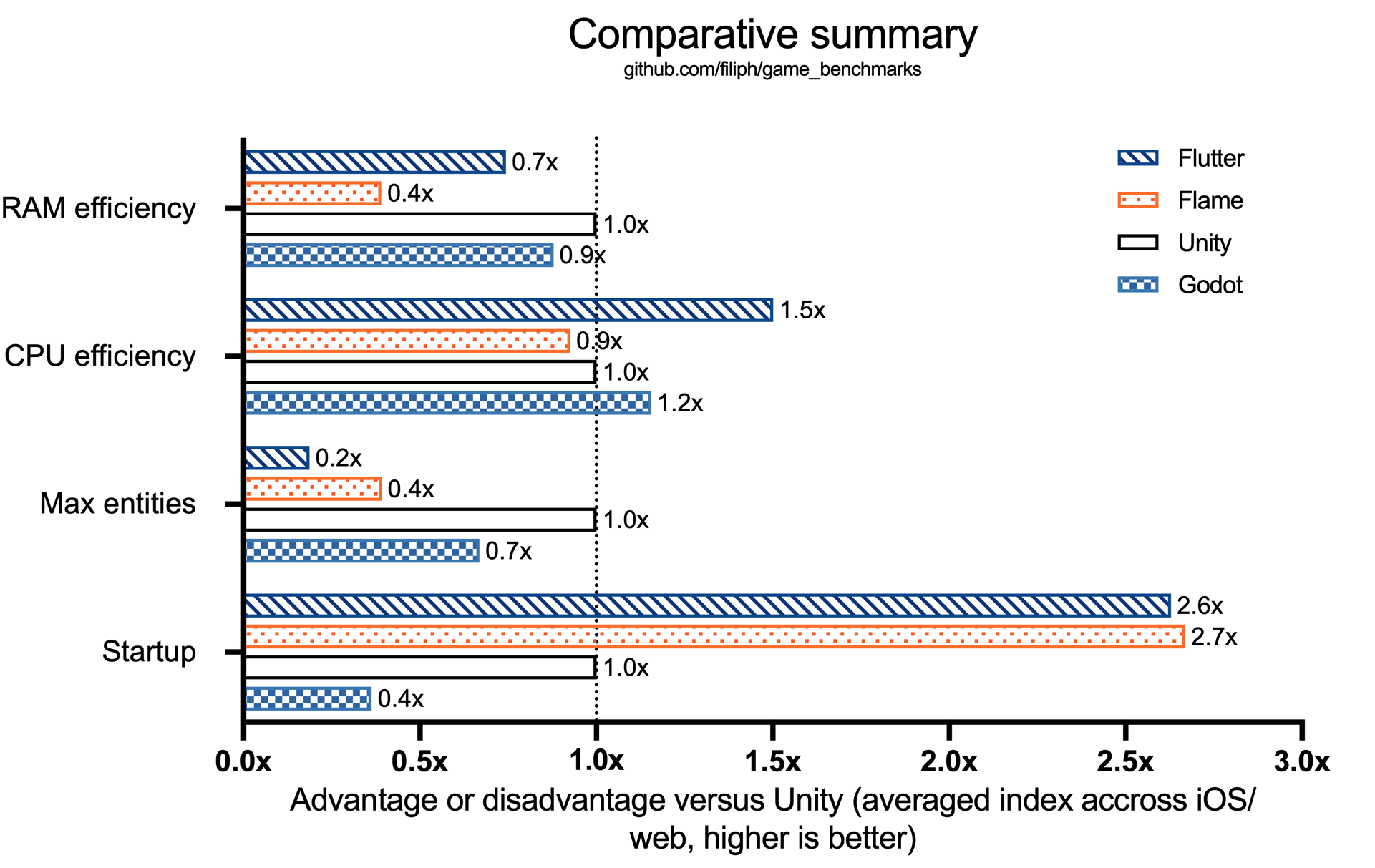

For the graph above, I merely averaged the iOS and Web results for each game engine, and converted them to an index where Unity’s result is always 1.0, better results are higher, and worse results are lower. For example, the graph shows that Flutter can show 0.2x the number of wandering entities before hitting frame drops (this number is an average for web and iOS) and it’s 2.6x faster to launch the game.

If you wonder why the benchmarks are listed in reverse order (from RAM to Startup), you’re not alone. I’m using a graphing software that I’m not entirely familiar with. I tried to change the order and failed.

The way I compute the index is as arbitrary as it gets. Who says that an engine is 2.6x “better at startup” than Unity because it happens to get to the first interactive frame of an arbitrary project in 1/2.6 the amount of time on iOS and web? Nobody, hopefully. The graph only serves as a quick, glanceable summary of the benchmark results. The real meat of the benchmark is above, with the individual measurements and their context. (And, for some of you out there, with the source spreadsheet for all those graphs.)

Therefore, if you see anyone sharing the summary graph above and saying things like “Flutter is 1.5x more CPU efficient than Unity” or something like that, you have my permission to ignore whatever that person says forever. They either have poor text comprehension skills, they’re prone to signal-boosting without reading the whole thing, or they’re hyping. In either case, they’re not worth your attention.

I’m glad my benchmark identified some areas of improvement for Flutter, especially the memory reclamation issue on the web.

It’s also good to know that Flutter, despite its roots in app development, enables relatively busy games. It can’t reach Unity or Godot, but I don’t think anyone is really expecting that at this point. Flame can support about half the entities that Godot and Unity can — but that’s still quite a lot of entities. Frankly, I was half-expecting a fraction of that number. When using vanilla Flutter on the web, the disadvantage is a full order of magnitude. The moral of that is this: if you’re building a busy action game with hundreds of entities, maybe don’t implement it as a Stack with Positioned widgets in Flutter? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

This brings me to what I expect is the best fit for Flutter and Flame as game engines: lower-intensity games with relatively few entities but engaging graphics. Think Slay the Spire, Balatro, FTL, Papers Please, Kingdom of Loathing, Fallen London, and the like. (These also happen to be some of my favourite games of all time.) Flutter is more than powerful enough to run these types of games. It also allows these games to launch in fractions of a second, and consume less mobile battery on average. On the web, things are less peachy but once the memory issues are addressed, I think a lot of the rest of the problems will follow. And it’s nice to know that Flutter games can run on any website, unlike Unity and Godot games (see the note about SharedArrayBuffer above).

I just learned this month about Drakontias, a Flutter game that’s being built by a tiny 2-person team (Cecilia & Leo Sanders). The same day I found out about Drakontias, I learned that Lukas Klingsbo (of Flame engine fame) won the first prize in the well-sponsored LG webOS TV hackathon with his Signs of Magic game. Not only am I looking forward to playing these two particular Flutter games — I’m also hoping to see a lot more of such gems in the future.

Thanks for reading to the end! Now go get building.

— Filip Hráček

September 2024