Filip Hráček / text /

How to playtest a video game

First things first: playtests aren’t demos. Demos are supposed to demonstrate how cool something is. Playtests suck. You get access to a game that largely doesn’t work yet. Things aren’t explained well (or at all), gameplay is still clunky, and there are even more bugs than usual.

That said, being part of a playtest can be an exciting thing. You’re able to play something way before anyone else, you can give early feedback, and you can see the game evolve to its final form. You’ll learn important things about how the gamedev sausage is made. You will also become a big reason why the game makes it to a release, and why it doesn’t suck when it does so.

So here’s some advice on how to do playtests right, as a player.

Record

If at all possible, record your screen when playing, or at least take copious screenshots. The developer knows their game inside out, so often they notice problems that you don’t. For example, there’s something that the developer thought you’d notice but you clearly don’t. That’s a problem that must be addressed. Also, bugs are easier to fix when the developer sees what preceded them. A playtest video also allows the developer to take a look at the footage in its entirety and ask such questions as:

- “Are some parts of the playthrough too boring?”

- “Does this look like the kind of gameplay I’m envisioning?”

- And so on.

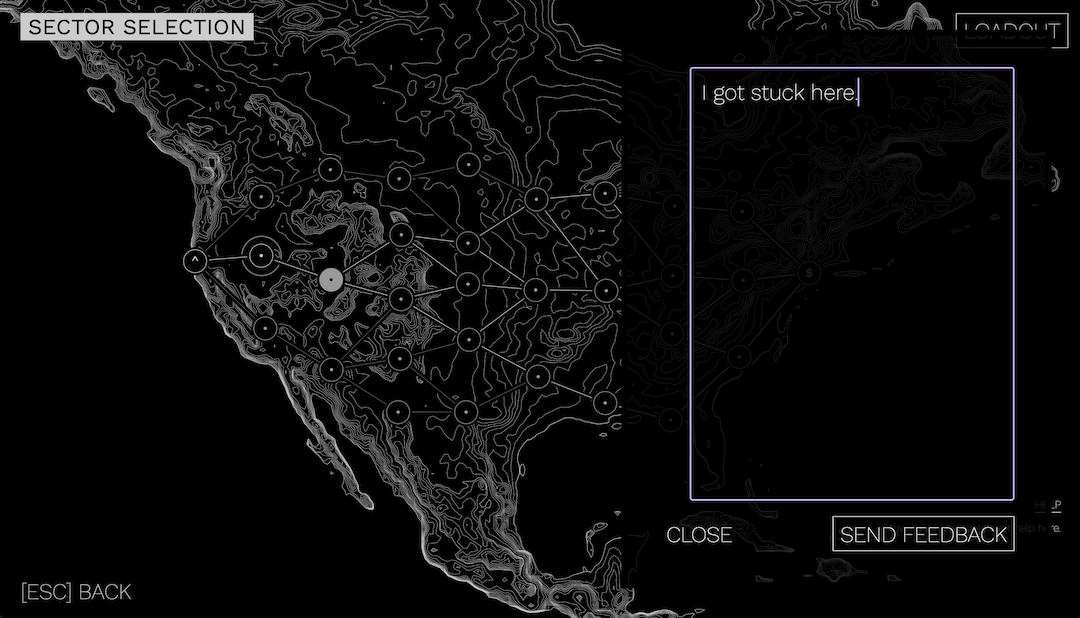

Also, some games let you send feedback right from the game (press F1 in my game to do so). This kind of feedback, while not as rich as a video, is fantastic because it comes with internal logging and other important context.

Expectations are important

When providing gameplay feedback, always be aware of your own expectations, and make them known to the developer.

An early playtest game doesn’t yet have the chance to express the “promise,” the genre, the intended gameplay, that it brings to the table. So it’s quite possible for you to pick up a playtest and go “nice, I’m going to enjoy this Action RPG” when in fact you’re playing a tactical simulation. This can lead to confusion and frustration.

It’s like chomping into a delicious-looking apple pie only to realize it’s a meat pie. Both recipes are delicious, but your expectation wreaks havoc on the experience. Always tell the developer if your expectation about the game (from the Steam page, for example) didn't meet reality.

Understand the goal of the playtest

Game development is all about testing hypotheses. At first, they can be technical. It’s like people in the early 1990’s hypothesizing that a personal computer could run real-time 3D graphics at acceptable frame rates. Only after they (Looking Glass Studios and id Software) corroborated this technical hypothesis could they start figuring out how to make a game from this technology (Ultima Underworld and Doom, respectively).

A lot of the time, the game developer’s hypothesis will be revolving around the concept of fun.

- Hypothesis: this new mechanic will be fun to play with.

- Hypothesis: adding this feature will increase depth without sacrificing fun.

- Hypothesis: this new version of the mission is more fun than the current one.

When playing, try to make mental notes of things that might be helpful to the developer.

- Are you becoming bored?

- Does something sound exciting but then isn’t as fun in reality?

- Does some action in the game feel like a chore?

Don’t hold back. Any good game developer would rather take an uncomfortable truth early than release a bad game later.

See past the current state

When playing an early playtest, you’re playing an incomplete game. It is really helpful when playtesters can identify parts of the game that are clearly “under construction” and see past them.

Some playtesters get hung up on things that just aren’t ready yet. The reality is, no game developer can afford to only playtest the game after all the bells and whistles are in. Sometimes, it’s obvious. An early version of the game will not have a tutorial, for example. Other times, it’s less obvious. Music is often missing in early versions of games. Yet audio is a big part of the play experience, so playtesters may feel like the game is somehow distant or bare just because, subliminally, they miss an audio track.

Here, it’s helpful if you have game development (or general creativity / product) experience. That way, you’re aware of how hard it is to “flesh out” something, and you can spot these incomplete things and extrapolate.

It’s not a critique session (at first)

When playtesting and, ideally, recording your screen, try to really focus on continuing the gameplay. Some players tend to stop in their tracks to give ideas or to critique a particular part of the UI. Those thoughts are valuable, but not if it stops the gameplay. It’s better to save the critique until after the play session ends.

It’s not because game developers don’t want your critique. But stopping mid-play to give a lengthy opinion is not a very realistic playtest.

Problems over solutions

When you identify a problem, focus on reporting the problem. Let’s say you get bored playing a level. Tell the developer when you got bored, what you were doing, and if the boredom was excruciating or just barely noticeable.

You may suggest remedies, of course, but don’t jump to that too early. Don’t drown the juicy stuff about the problem with ideas for solutions.

The thing about game development is that almost no problem has a simple solution, even when it might seem so from afar. If you ever wondered why this or that game developer doesn’t just fix that one problem already, you've encountered the issue. Generally speaking, game developers aren’t lazy. They just deal with problems that are much harder in reality than they seem.

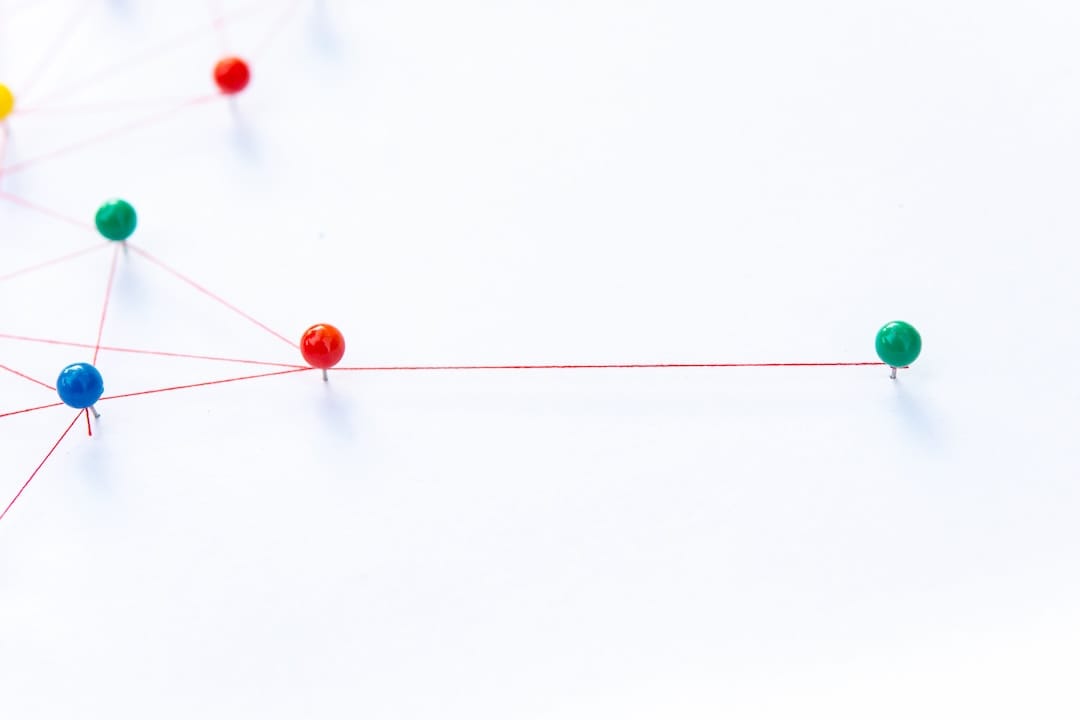

I like the metaphor for a game as a bunch of push pins on a bulletin board, tethered to each other with strings. The pins represent the different parts of the game: the different mechanics, the art style, the sounds, the music, the story beats, the enemy strengths, the AI, and so on. The strings between the pins represent how all these parts depend on each other. You can’t change a game mechanic without influencing other game mechanics, balance, play time, etc. You can’t change music without influencing sound effects, theme, the story’s emotional impact, etc. Almost everything depends on everything else.

Now imagine trying to move one of the pins a little bit to the left. You can’t. You’ll have to move ten other pins. Some pins are so central that moving them will basically move the whole game.

That’s why, sometimes, solutions offered by players, even when they seem obvious and rational, are not acted upon. You’re asking to move a push pin that, in itself, really should move, but unfortunately it would mean that the whole game needs to change. The game developer would much rather keep building the game that they have than to completely rewrite it to something else. So they try to find solutions that move fewer pins.

Don’t forget what it’s all about

I’m one of those obnoxious people who actually take video games seriously. I see play as a primordial way of learning and training our brains. But even I understand that the main element of play is fun, and without fun, there is no real play. So if you’re not having fun playtesting, say so to the developer, and bow out. If you’re going not to have fun, might as well do it in the real world.

PS: If you’re a game developer, I recommend reading How to get feedback on your game by Chris Zukowski for the opposite look on the same problem.

PPS: If you’re interested in play-testing GIANT ROBOT GAME, please send me a note! But if you’d rather go it alone, you can always try the game on Steam Playtest or at itch.io.

— Filip Hráček

October 2025