Filip Hráček / text /

Making a tile-based game look like it’s not

I’m building an indie game but I don’t want it to look like an indie game.

Not that I have budget for AAA graphics, mind you. I merely want to avoid breaking immersion by using tiles. Tiles are a tell-tale sign of “gaminess”. And I want my game to seem like a simulation, a UI that might be used in real life. I don’t want it to look like a video game.

Unfortunately, it’s basically impossible to make a 2D tactical game without tiles. If nothing else, the game AI needs tiles to make sense of the space, and to plan things like movements and attacks.

Tiles are also very useful for path-finding. Technically, you can do pathfinding through any graph of nodes, but in practice, tile-based A* is by far the most well-understood and simplest-to-implement approach.

So, if you look deep enough, most games are actually tile-based. And so is mine. It just tries to hide it as well as possible.

Just don’t render the tiles

Thankfully, even when you have tiles, it doesn’t mean you have to show them to the player. If the tiles are small enough, the player doesn’t need to know, right?

Well, yes, but there are a few things you need to solve.

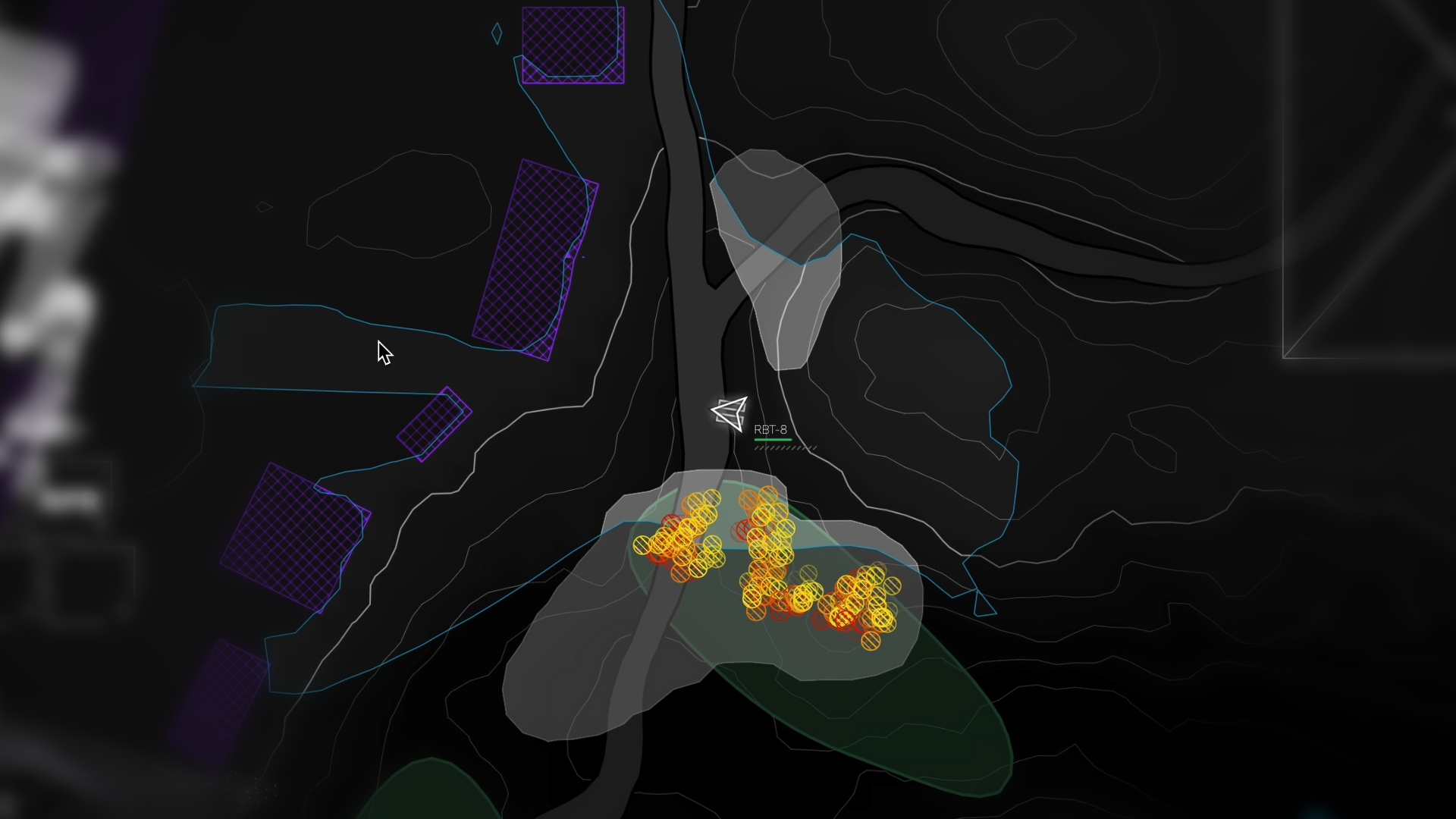

First of all, if you simply implement tile-based path-finding and let entities in the game follow it precisely, the tiles will resurface through that movement. Everything in the game will go in the 8 major directions (north, north-east, east, ...), and on a grid.

String-pulling

Thankfully, we can learn from AAA games. Those use something called string-pulling. The way it works is this:

- You plan the path tile-by-tile, as normal.

- When a game entity follows the path, instead of slavishly going from one tile to another, it picks a waypoint somewhere ahead on the path, and heads towards that point.

- If the entity gets near enough the waypoint, it moves it further ahead on the path.

- If something blocks the entity’s path toward the waypoint, it picks a waypoint that is earlier on the path.

This way, entities almost never go in cardinal directions of the grid.

(In the debugging visualization above, the string pulling waypoint is visualized as a flat ellipse.)

The method is called string-pulling because it looks as if the entity is being pulled on a string that’s attached to something further ahead on the path.

Making paths less awkward

When planning longer paths on tiled grids, the path can easily looks like this:

START ▘▘▘▘▘▘▘▘▘▚

▚

▚

▚

GOAL

Classic path-finding algorithms (like A*) form this hockey stick that seems okay on tiles but looks really weird otherwise. No amount of string pulling will make this look right. Without tiles, the path looks like the entity is going out of it’s way for no apparent reason.

If you’re hiding tiles, what you want instead is something like this:

START▗

▘▘▘▚

▘▘▘▚

▘▘▘▚

GOAL

But path-finding algorithms on a tiled-based grid normally give you the hockey stick — because from their perspective, the hockey stick is the most obvious path, simply following the heuristic/cost function.

You can try to address this by fiddling with the A* algorithm’s heuristic/cost functions (read Amit Patel’s treatise on this), but this often results in paths that are barely better — and sometimes much worse.

The only true remedy that I’m aware of can be found in a little known research paper from 2022 called Path Counting for Grid-Based Navigation. It’s too complex to describe here in detail, but in broad strokes:

- The algorithm finds all the best paths from START to GOAL (in other words, it doesn’t end when it finds the first best path, but keeps going as long as there are other paths with the same cost). On a tile-based grid, there are often many paths with the exact same cost. Think about the hockey stick

\_, the inverse hockey stick▔\, and everything in between. - It then counts how many of the best paths go through each of the tiles. (Thus, path counting.)

- It then constructs the path through the tiles with the highest counts.

The resulting path always looks way more natural than the “simple” answers.

This is less efficient than a simple A*, of course, but for what I’m trying to achieve, it’s well worth it.

(In the debug animation in the previous section, you can see the path counting visualized with the vertical blue bars on each visited tile. The longer the bar, the more paths go through it.)

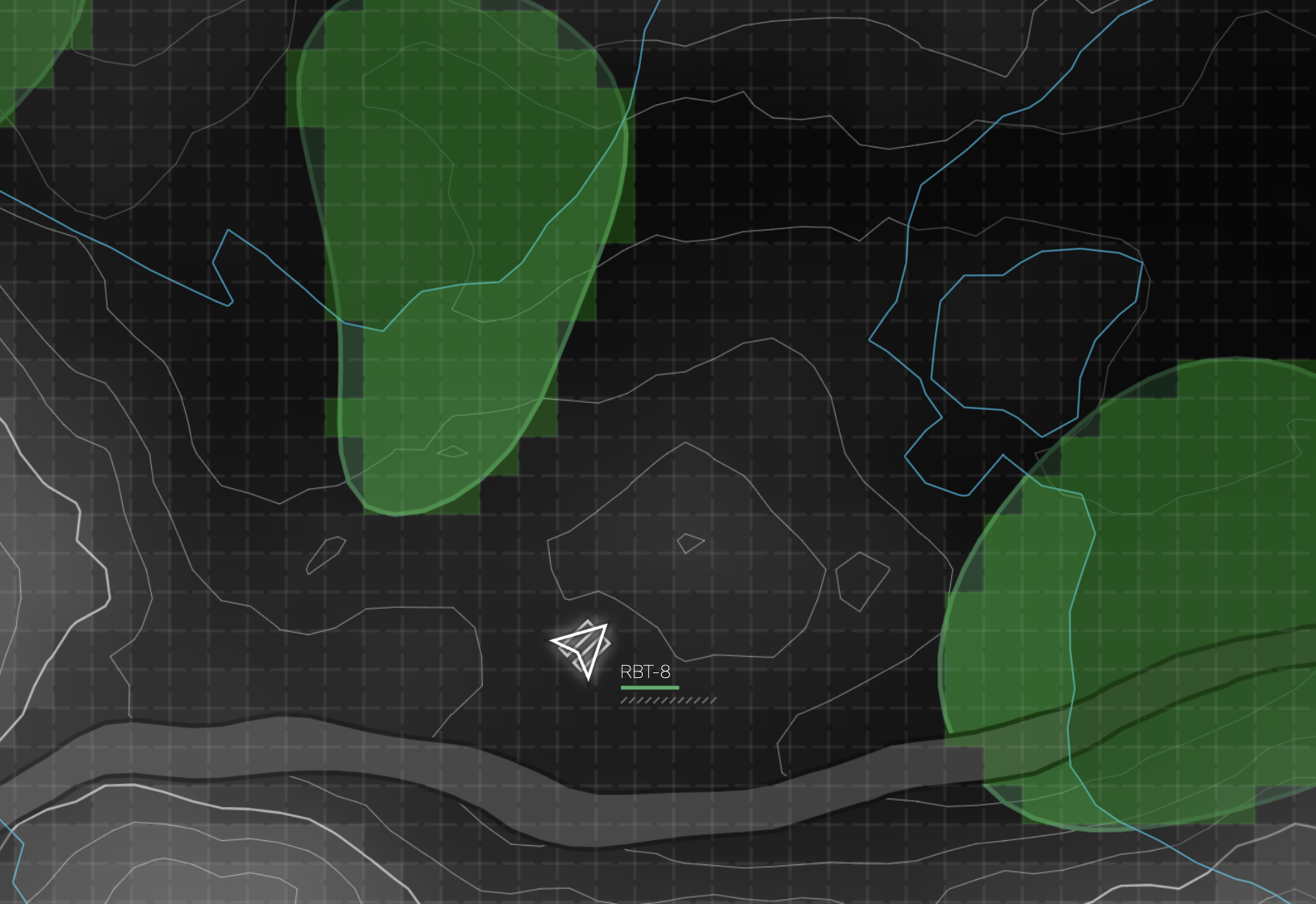

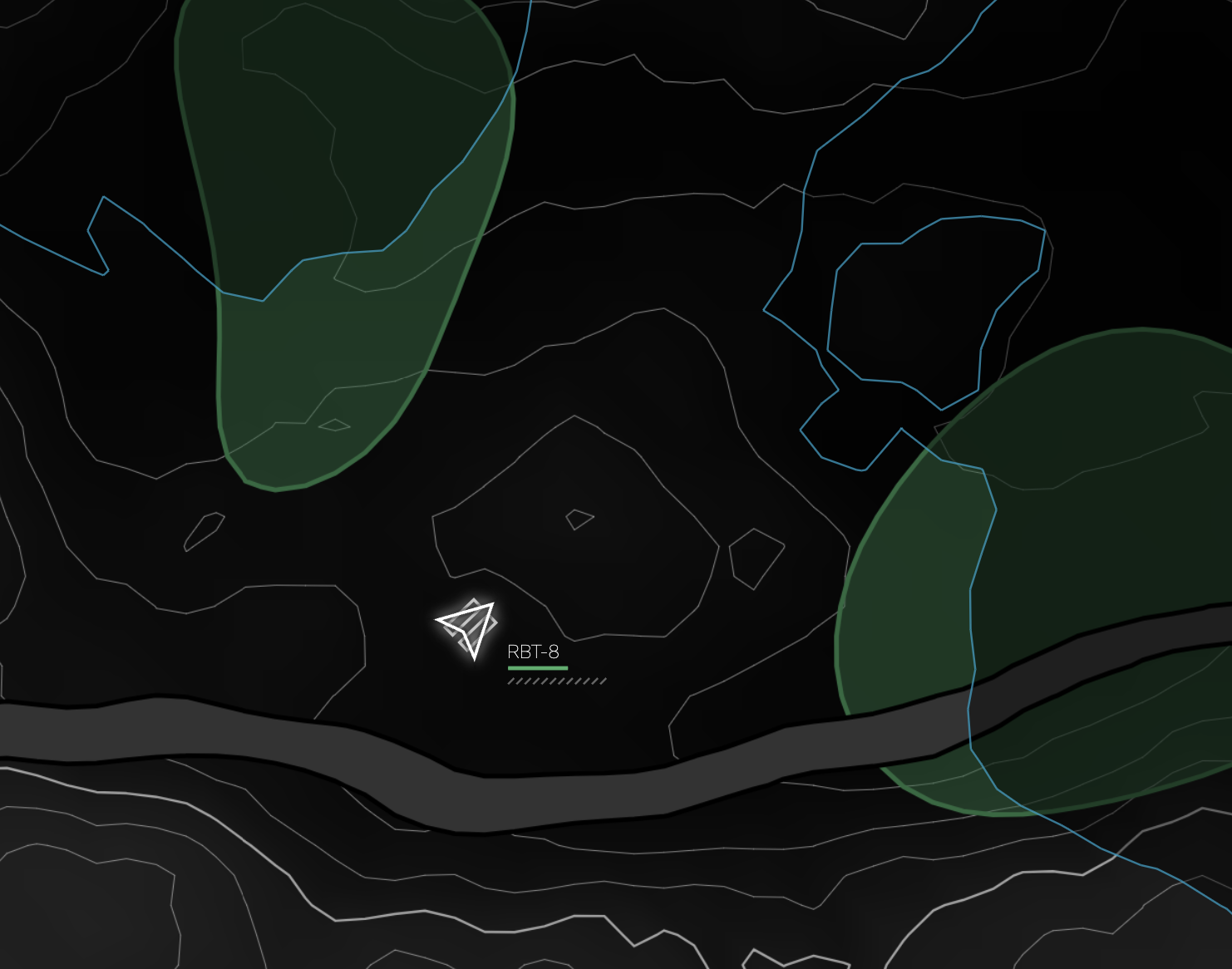

Making areas less tile-y

In a tactical game like mine, there are often things happening to areas, not just single entities. For example, in my game, a wildfire in a forest will generate smoke that blocks the player’s field of view.

You have three things that are areas here:

- The forest occupies an area of the map.

- The smoke spreads from tile to tile.

- The player’s field of view is also an area, with every tile being various degrees of visible.

If we rendered this through tiles, we’d be back to square one. A blob of smoke would become a jagged mess of tiles. Same goes for the forest and the player’s visibility field. Sure, we could use non-rectangular frontier tiles, such as ╯ instead of ┛, but these can’t really hide the truth from the player.

Very tile-y Better but still tile-y

┏┛ ╭╯

┏┛ ╭╯

┛ ╯

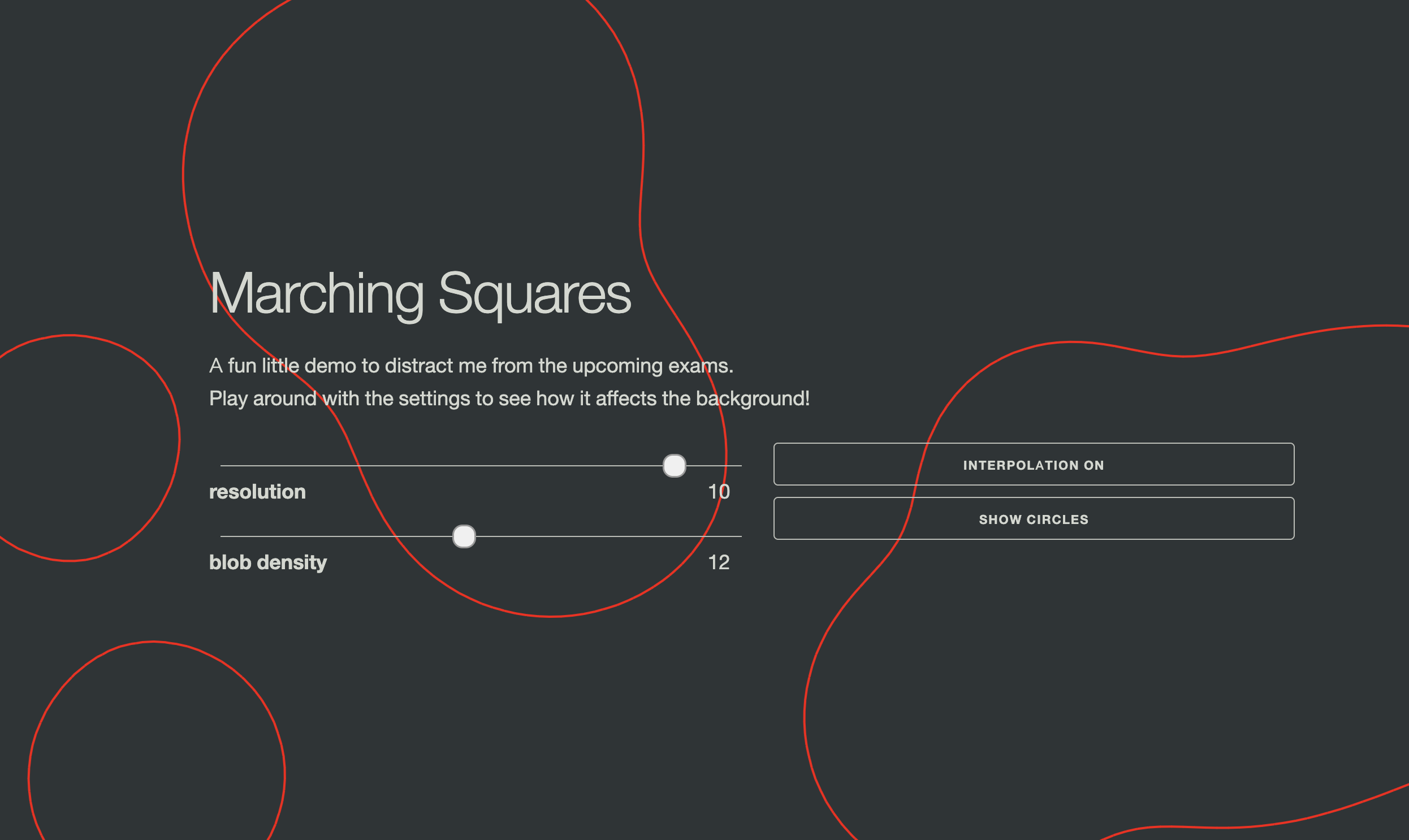

Thankfully, there’s the marching squares algorithm.

Once again, the devil is in the details, but in broad strokes, here’s how you can present the tiled-based world to the player.

- Instead of holding the information as a boolean (forest or not forest), you hold it as an SDF (signed distance field). A tile that is fully inside a forest has the

forestvalue of1.0. A tile that is at least a tile away from the nearest forest hasforestvalue of-1.0. And for the tiles that are on the frontier, theirforestvalue is proportional to how much “inside” the forest they are. For example, a tile withforestvalue of0.0is exactly on the border of a forest. Aforestvalue of-0.02is very very close to a forest but still outside. In other words,forestis the measure of “insideness”, with-1being completely outside and+1being completely inside. Yet another way of thinking about it is that theforestvalue is a signed (±) distance to the forest’s frontier, with the distance from within the forest measured in negative values, and distance from outside measured in positive values. Thus, signed distance field (SDF). - You render this by taking every square of 4 adjacent tiles, and rendering the frontier between them. It turns out there are only 16 different ways this can go. For example, all 4 tiles can be within the forest (

forestvalue is less than0on all four tiles), and so you simply render a green square. Or maybe the top-left tile is inside a forest, while the others are outside. So you render a◤triangle. You scale the triangle’s sides according to the values offoreston the appropriate tiles — so it’s not always the same triangle.

The resulting effect is very organic and, with small-enough tiles, can completely obscure the fact that it’s all tiles.

(You can visit this interactive explanation to play around with marching squares and see the code.)

You also get the additional advantage of more realism. The player is no longer able to min-max some game mechanic by standing at a very specific tile that’s surrounded by a very specific configuration of other tiles. Forests, smoke and visibility ranges flow naturally through the playing field, with billions of different tile-by-tile configurations.

Currently, I’m using the following signed distance fields (and their resulting marching squares) in the game:

- Forest

- Water

- Smoke

- Masonry (the presence of built structures, such as houses)

- Debris (the presence of rubble, such as when a giant robot walks through a house)

- Radioactivity (the presence of nuclear radiation, such as when a reactor explodes)

- Visibility field (to surface to the player the exact extent of what their player character sees - an important goal in a 2D tactical game with terrain and various visibility effects)

I could easily extend this list with things like weapon ranges, lighting, lava or territorial control. But of course, there’s complexity and performance cost of adding each additional layer. So I’ll probably stay with what I have.

More non-tile-y games, please?

I’m obviously not saying that every 2D indie game should now implement string-pulling, path-counting and marching squares. Making tiles explicit is often just fine, and other times, it’s the point (think Into the Breach). The simplicity and readability of tiles can be a superpower.

But I hope that maybe there’s an indie developer out there who reads this article and says, “hey, that’s neat!” or, even better, “this is what I needed to make my game idea work!”

— Filip Hráček

December 2025