Filip Hráček / text /

Memex is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed

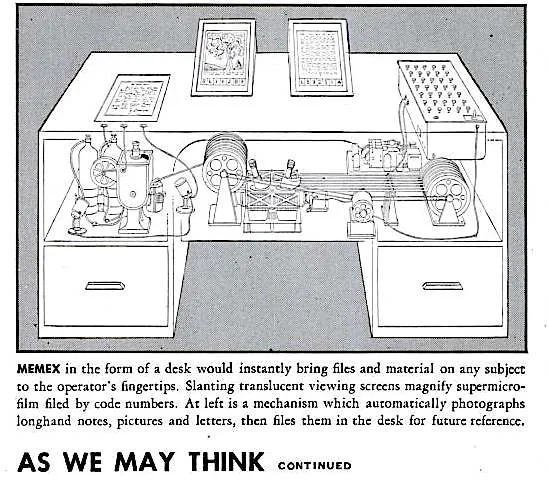

In 1945, Vannevar Bush proposed the idea of memex, a hypertext system. It came two decades before the internet and almost half a century before the web. Because of the time in which it was invented, it was envisioned as a mechanical device: a desk with cards and a mechanism for showing them to the user.

Vannevar Bush described a device which would store the users books, records, and communications. There was a concept of memex “trails” that linked from one document to another. Memex was to be an “enlarged intimate supplement to one’s memory”.

The concept of the memex was highly influential, eventually leading to the invention of the World Wide Web and its Hypertext Markup Language (HTML).

For this reason, some people assume that the web is an advanced version of memex. But in fact, the web is a terrible approximation of Vannevar Bush’s original vision.

Memex trails

The web is a hypertext, and one of the most influential inventions in human history, but it is not memex.

- On the web, documents aren’t yours. Almost universally, what you read on the internet is on someone’s else server. You cannot edit it, or annotate it.

- There are hyperlinks on the web, but again, they are not yours. They are added as simple, unidirectional links by the original authors of whatever it is you’re reading. You can’t add your own link between two pages on New York Times that you find relevant. You can’t create a “trail” of web documents, photographs and pages that are somehow relevant to a topic you’re researching. You can’t annotate a relationship between two paragraphs on two separate sites.

What Vannevar Bush proposed with memex wasn’t a publishing platform. It was a memory expansion device.

His “trails” are similar in concept to a physical binder that contains documents that you can freely annotate, highlight and interlink. Any given document can of course be in multiple different binders, and its annotations and links depend on the context. Even for a single person, every “page” can exist in several different forms, depending on what the person is researching or trying to remember at the moment.

Memex today

We live in a knowledge economy. This blog is primarily for developers, and software development is in many ways a research job. But almost any other occupation that pays these days has some element of attaining and using knowledge. You’d think we’d be all over memex and its idea of memory expansion. But chances are pretty high that this is the first time you’re hearing about memex at all, or that the last time you heard about it was years ago.

There are projects that explore this space, of course. The most obvious descendant is Ted Nelson’s Xanadu project, a piece of software more than 50 years in the making. You can see its 2016’s incarnation in this video.

I think you’ll agree with me that, while Xanadu is a lot closer to the idea of memex than the web, it’s kind of underwhelming as a piece of software. I remember playing with it a few years back, and I just didn’t find it that compelling.

There are more pragmatic descendants of memex. The Federated Wiki project is one. The various personal knowledge bases are close to memex, too.

And look, if you’re in the mood of exploring new software, you should stop reading now and see if any of the above is a good fit for you. I know the urge to try something new and shiny. Especially in productivity software, I can seldom resist. I have used about 4 different TODO apps and over 5 different text editors in the past 10 years alone. So, go ahead and indulge yourself if you need to.

But this article is not about any of these direct descendants of memex. The memex of today is way more pedestrian.

…

Here’s the thing. If I’m being honest, most of my experiments with the different memex descendants mentioned above just kind of faded after a few weeks or months. And the reason is not just habit. If they were such a huge boon to my productivity, I’d change my habit the same way I changed it for better IDEs, better social media consumption strategies, or better terminal defaults.

No, the reason those shiny new apps don’t stick is interoperability.

Interoperability

Interoperability is more important than features. A piece of software that works with your existing files, and which people around you can use, will generally win over some new way of doing things that you first need to migrate to, and then also ask others around you to migrate to as well.

The clean slate and the excitement that a new piece of technology gives you is tempting. But no matter how cool a piece of software is, if you can’t work with others, then you’re paying too much for the thrill.

Imagine that you and I are working in the same company. I tell you there’s a new project for us two to work on. I explain it to you and you get reasonably excited. And then I tell you that I’ve started a new “bloorp” in BloorpyBase, a piece of software from 2012 that almost nobody uses. You grudgingly install BloorpyBase. The app doesn’t use the same keyboard shortcuts you’re used to. The shortcut normally assigned to adding a comment instead minimizes all windows. Sigh. You try to link some exploratory source code to it, but BloorpyBase only works with Mercurial. Sigh. You read some of my initial thoughts and try to respond but you don’t know what’s the best way to do it. Should you create another bloorp? Should you make a suggestion, or an edit? You spend half an hour reading a “How To Bloorp” guide on the internet but come back empty handed. Sigh.

Unless BloorpyBase gives the average person a significant productivity boost, it’s not happening.

Back to basics

Alright, so what is it that we really want from memex? It must be easy to:

- edit content in the memex

- add completely new pieces of material to any given memex “trail”

- link form parts of the memex to other parts of the memex

- comment on specific parts of the memex

And when I say these things must be easy, I mean they must be easy for the average person. Not just for you and me and a couple of other nerds. For everyone.

It’s fine if some parts of memex are hard to use or require training. But the basics should be obvious and accessible. The learning curve can be steep at some point, but it must be gentle or flat at the very beginning.

Memex is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed

If you look back at the list above, you’ll realize that these things are already very much possible. They might not be in a single shiny app, but that doesn’t matter. (In fact, it’s probably better, in many ways, that today’s memex isn’t a single app. We’ll get back to this later.)

To create a new memex “trail” in the year 2020, just create a shared folder (in Zoho Workdrive, Dropbox, Synology Drive, Google Drive, OneDrive, iCloud, etc.) and put some documents in it. That’s it.

I know: it’s not glorious. It’s not shiny. It’s just a boring old folder with boring old documents. But I hope to persuade you that it’s good enough, and that you don’t need to wait for some vaporware to work the way Vannevar Bush imagined in 1945.

How to memex

Not everyone who is using a shared folder is using it as a memex. In fact, I estimate that 99% of people don’t.

To really take the technology of today and use it the way Vannevar Bush envisioned, you need to use it in a specific way. I’ll walk you through it here, but you must know that this is just one way, and it’s not very rigid. No shared folder software forces you to use it in any given way. You must train yourself. You must invent your own system on top of what technology you already have, and you have to persist in applying it.

Imagine that you have a project. It could be anything. For example:

- Significantly improve the performance of your employer’s app

- Delve into some legacy code for the first time

- Analyze viability of a business idea

- Decide on the next car to buy

- Learn SQL

- Track your kid’s progress

- Learn as much as you can about your own metabolism

Note how some of these projects are work-related, others personal. Some will be solo, others will be pusued in a team. Some have a concrete deliverable, others are ongoing. But all of them require some research, and would benefit from recording the acquired knowledge.

As I said above, to create a new memex trail, you just create a new shared folder. I highly recommend giving it a memorable, descriptive and searchable name. For example, “website 3” is short and easy, but “example.com redesign 2019” is better. In some cases, you may want to invent a codename. For example, “Project Gandalf” is more memorable (and fun) than “kid progress tracker”.

To make this more concrete, I’ll pick a single project and I will spend the rest of this “how to” section describing it in detail. I think you won’t have any issues generalizing this to other projects.

My project pick is “significantly improve the performance of your employer’s app”, and I’m going to call it “Project Sloth (2020 perf optimization)”. Since this is a work project, I create the folder in my company’s shared drive.

At first, I just add a single document in this folder. This is the project’s main document, or “index”. It probably has the same name as the folder. It should serve as a guide to the project, for others in the company as well as for me (when I look at it 2 years from now). In here, I describe the project and I link to other stuff inside the folder (and outside of it, if needed).

The “Project Sloth” document should probably start with some “Background” section. It can be a single paragraph that says something like:

In 2019-2020, we have seen a sharp increase of reports from our users that the app is too slow. (Link to some evidence to back up this claim, ideally.) On a meeting on October 18, 2020, Alice, Bob and I decided that this needs to be addressed. I volunteered for this project.

The index document then lists some basic information (e.g. “app was built using technology X”) and goals (e.g. “decrease startup time on phone Y by 50%”).

The rest of this document can be a “trail” of content. For example:

- Initial metrics and the methodology of measuring them

- Quotes from articles as I learn more about how to improve performance in technology X

- Some failed ideas and why they were rejected

- Pseudocode

- Meeting notes

Ideally, this content is structured with thematic sections. But I can start with just chronologically taking notes for now.

Pretty soon, my single document does not suffice anymore. I need to add more supporting data into my folder, and link to it from the index doc.

Once I start comparing different approaches, it makes sense to create a spreadsheet. It lists the different things I’m considering, their pros and cons, and some guesstimates. I link to this spreadsheet from the index doc, where I just summarize the final outcome of my analysis.

Later, I write a benchmark harness. At this point, this is just an ugly bag of shell scripts. They could go into a throwaway repository, but I can also put them in a subdirectory of my project’s folder. In any case, I need to link to that code from my index doc.

Let’s say that this benchmark harness has the ability to check my company’s app’s performance at any given commit in the history of the app. I let the shell scripts work over the night, producing a huge amount of historical data. This could be another spreadsheet, but if it’s really a lot of data, it could be a SQLite database. I place the database file in — you guessed it — the project’s shared folder, and link to it from the index file.

Pretty soon, the “Project Sloth” folder is teeming with content. Original documents, code, PDFs, presentations, screenshots, spreadsheets, data files, iPython notebooks, videos. All of these are relevant to our project, though some of them may be symbolic links (in other words, they also exist in other folders in my company’s shared drive). The index document links to all of them. It summarizes the most salient points of each: it reproduces a graph here, or a quote there.

I have my memex trail for this project.

Use your memex

Even if I deleted the folder at this point, it would all still be a beneficial exercise. By putting all of this together, I need to organize my own thoughts. I get to see everything in context. I understand the problem more clearly.

But I’m not deleting the folder, am I. I can now direct other people in my company to have a look. They might help, by giving me feedback, adding more data, or by throwing resources at me. If the project becomes important enough to get a team, new team members have a much easier time getting on board.

And when I inevitably need to review something a few months from now, I know exactly where to look. For example, I will want to measure whether the app is actually getting faster, and I will want to use the exact same methodology and code as at the start. Thankfully, both are right there in my memex trail.

The human element of memex

Memex is here, it just won’t happen automatically. There’s no magical piece of software that will do that work for you (and maybe there never will). You will have to learn how to summarize, organize and explain. You will have to decide which problems require which files types (document, spreadsheet, image, etc.). You have to have the perseverance to continue updating your trails.

It will hurt. It will suck. It’s not like starting to use a new, elegant tool on some pet project. A lot of brain power needs to go into this, and it’s mostly boring, menial work. But hey, nobody said this stuff is easy. Not even Vannevar Bush. None of us are entitled to easy work.

But where is my cool dashboard?

Look, I love Minority Report’s vision of future work interfaces as much as any other geek. I’m also really into cool-looking dashboards.

But even I have to admit that their utility is limited. Dashboards are not nearly as flexible as your operating system’s window manager. Just open the links in separate windows and voilá: you have your own bespoke, interactive dashboard. You’re like Tom Cruise in Minority Report, except your interface is a little more boring (and requires a lot less arm strength to move a window).

Add a second monitor to your setup if you can, and you’re more productive than most of your sci-fi movie heroes. (Have you ever stopped to think how incredibly frustrating it would be to use a Star Trek-level UI for anything else than browsing a simplified encyclopedia?)

But isn’t this something we could have been doing since about the late 1990s?

Yes. (Although some things, like interlinking between documents, were a lot harder back then.)

What about Evernote / OneNote / SimpleNote / Dropbox Paper?

If your organization uses any of these apps extensively, that’s great. I think it’s very close. As far as I know, these software packages lack the “shared folder” part, which is a show stopper for me (many of my projects have some files or code involved). But I love Evernote’s editor for taking notes, for example. Much faster than Google Docs.

UPDATE from 2023: Evernote’s editor used to be much faster than Google Docs, but became slower. I now use Obsidian for my note taking and editing. Same idea.

What about just using Zoho/Google/Microsoft/Apple for everything?

All of these suites definitely get additional value from integrating several different apps into one. For example, you can paste a chart from a Google Spreadsheet into a Google Doc, and the chart will be automatically updated.

But:

- I don’t see the more integrated features used often enough — a simple screenshot and a link will suffice most of the time, for example, instead of trying to get a self-updating embed to work.

- There is always something missing in these suites — can’t run a bash script saved in Google Drive, can’t have a huge database in Spreadsheets, and so on.

- Vendor lock in is real. A simple rich text document can be easily ported. A heavily feature-dependent thing, not so much.

I do use many of the niceties of the Google apps ecosystem every day. But it’s not memex, and shouldn’t be. We have too much aggregation as it is.

Why not have everything in a bespoke cloud environment?

Everything is possible. I could have something running in the cloud that could run the aforementioned bash scripts in a Google Drive folder, and update other files in that folder accordingly.

But setting it all up is a pain. Yes, you can run an arbitrary program in the cloud, then hook up an online spreadsheet to use this output. But remember, we’re talking about research projects. You’ll have about a dozen of those every year. Each will be different. For example, for one of my past project, I needed to build a bespoke python GUI tool to help me categorize hundreds of websites. Sure, I could have built a small web app. But building a tiny pygame app was much, much easier.

But, do I have to?

You don’t need memex. You don’t need to do any of this shared folder nonsense. 99% of people don’t, and many of them are doing just fine in their careers.

On the other hand, memex is something that will give you an edge.

- Your decisions are backed by sources and data.

- You can go back to these decisions much later.

- You can get someone’s review of your ideas in their entirety, instead of asking question by question.

- You gather knowledge much faster than you would by just asking stuff.

- If you ever end up in a large organization, these tools are a huge multiplier of your efforts. In a huge organization, it is unlikely you will be able to talk to everyone you need to reach. But your memex on a particular topic can easily reach hundreds of people.

- When you start putting things on a page, and backing them by data, you’ll find you have to be a lot more precise about your reasoning. You can’t just hand-wave some stuff like you unwittingly do when you’re just pondering something in your head.

- You’ll train yourself to “do the (boring) work”. This is important. Self-discipline is what separates high-performers from the rest. (There’s a book about it.)

- You’ll train yourself to accept criticism. By putting your reasoning in a document and letting others see it, it’s now open for all. All the warts and errors are now out there.

- Being able to back decisions by data and research and persuade others (again, by data and research) is one of the important stepping stones to becoming a senior developer or a tech lead.

So, again, don’t wait for memex to come in a neatly tied package anytime soon. And know that you can build your own memex today, by combining widely available software, a loose system of working with it, and perseverance.

— Filip Hráček

October 2020