Filip Hráček / text /

A techie’s guide to keeping young kids away from technology

There’s this assumption that people in the tech industry just automatically immerse their kids in technology.

Nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, the technical people I know are actively trying to shield their kids from technology, especially at an early age. Many people in Silicon Valley do it, many of my friends do it, and so do I.

There are 2 reasons for this “paradox” (which, as usual, isn’t really a paradox):

- Tech is our expertise, so we understand some of the nuance surrounding it. Yes, modern tech (like smart devices, the internet and LLMs) can be incredibly useful and mind-expanding in some situations. That doesn’t mean it can’t be harmful in others.

- Shielding your kids from technology is actually quite hard, and requires way more technical expertise than it should, to be honest. Techies do it more than others simply because they know how.

In this article, I want to quickly go over some reasons why parents should limit their kids' technology use, as well as my practical experience and advice. Towards the end, I share an open source project that I built in 2024 that helps me a ton and that I hope might be useful for others.

Giving access to tech can’t be bad, right?

First, let’s dispel the myth that technology must necessarily be good for kids because that’s what they’ll be using their whole life. “Giving a kid an iPad in 2026,” the argument seems to go, “is like giving a kid a chess set — or a book, or an abacus — in the past.” The idea being that the kid is learning important skills.

Are they, though? What important “skills” does a kid learn from watching Paw Patrol and popping virtual bubbles on an iPad for hours every day? 15 years back, we all collectively fawned over the fact that “even a toddler can open an app” on a tablet. Instead of having to operate a mouse (having to link the movement of the mouse with the movement of the cursor on the screen), the toddler can just touch the brightly colored image on the screen. Amazing.

Does anyone really think that this is how a tech wiz career starts, though?

That’s like saying that your kid is on its way to becoming a weightlifter because it can pick up a piece of paper. The bar is just too low here.

And the evidence seems to be with me on that. People who grew up in the iPad era are emphatically not more tech savvy than the generation before them. A recent study showed that Gen Z are worse in digital security than Baby Boomers (and that’s saying something). And it’s not just security. I've seen (admittedly anecdotal) evidence that the younger generations — who grew up surrounded by modern technology — tend to have worse tech skills than, say, Millennials.

Ok, but at least it’s not actively harming them, right?

How can it be that giving a kid a tool is not unreservedly good for them? It’s not just the ease of use. It’s also the huge qualitative leap between tools of yesteryear and technology of today.

When you give a kid access to, say, YouTube or TikTok or the latest mobile game, you’re not giving them a neutral tool, like a hammer or a spatula. Much of tech today is optimized for engagement, for money spend, and for persuasion. Imagine if there was a spatula that was designed by teams of psychologists and engineers to subtly nudge you to make more unhealthy food, more often. That’s absurd, because that’s not possible with something as simple as a spatula. But it’s very much possible with modern silicon.

It is noteworthy that many digital platforms are designed to tap natural human attentional, impulsive, and reward processes, which in turn leads to habit formation and repeated use of the platform. 13,19,20,21,22,23

Basically, it’s your kid versus teams of experts who've by now had over a decade of experience in making technology more “sticky” (industry term for addictive).

At this point, it’s pretty safe to say that screen time is linked to ADHD (see aside below for important caveat). Researchers are first to note that the study of screen time effects is in its infancy but after reviewing the most recent articles, I think you’d have to be very pro-screen to think that screen time isn’t bad for kids.

The results showed a statistically significant between-person effect of social media use, television viewing, and video gaming on ADHD symptoms. Results also indicated a statistically significant concurrent within-person effect of social media use, television viewing, and video gaming on ADHD symptoms. Computer use showed no statistical significant association with ADHD symptoms at between and within levels.

(Ibid.)

I’m quoting from Wallace 2023 here but there’s also a more recent article from 2025.

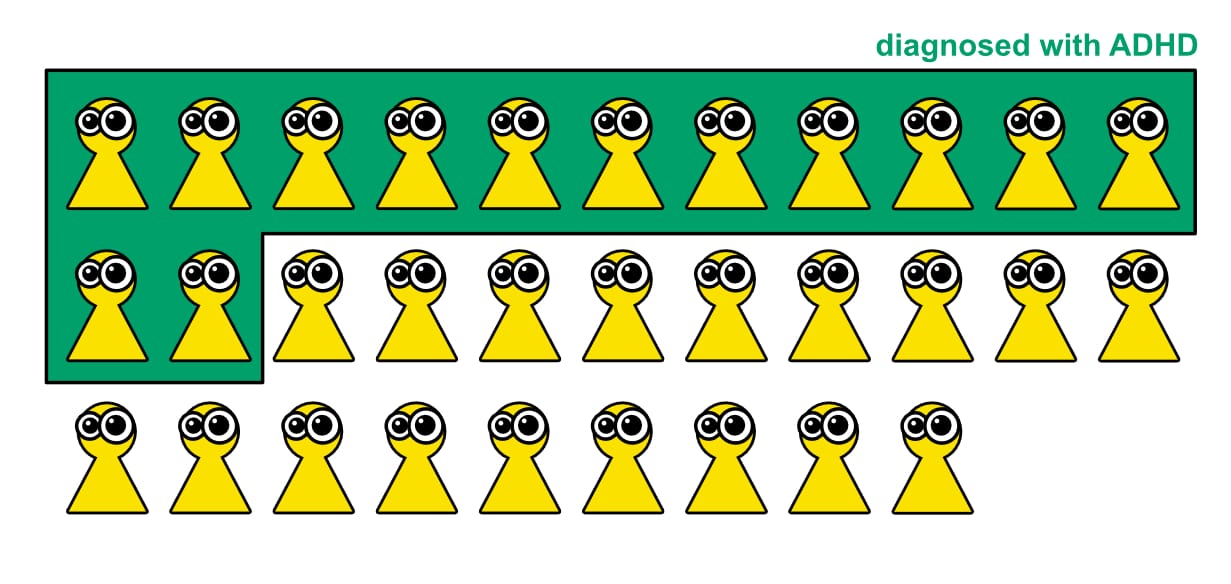

Aside: Based on reader feedback, I want to make something very clear. Screen time does not cause ADHD itself. The disorder is mostly genetic. But the scientific research I’m quoting here gives strong evidence that screen time exacerbates symptoms of ADHD. So, we’re talking about ADHD kids that might go undiagnosed or be on the lower end of the spectrum having their ADHD symptoms heightened by screen time. The resulting effect is that more kids are diagnosed, and ADHD symptoms tend to be worse. Saying that “screen time causes ADHD” is incorrect. But the effect of screen time is that we see more of ADHD and the cases are more severe.

Just yesterday, I talked to a mother of a kid who goes to a nearby elementary school. She told me that out of 28 kids in the class, 12 have ADHD. Now, it’s important to say that ADHD is a spectrum and yes, that diagnosis wasn’t really a thing a few decades ago. It’s not that there was zero before and now there’s 12. Screen time is clearly not the only source of worsening ADHD symptoms. I’m sure we had at least one kid in my class in the 1990s that would be diagnosed with ADHD today. But that doesn’t nullify the fact that these attention issues are more prevalent today.

And it’s a problem. A teacher I talked to a few years back said he can definitely feel the difference, even among the kids with no formal diagnosis.

People sometimes like to pretend that ADHD is a “superpower”. I get when an ADHD-diagnosed kid says this. It helps to be positive about these things. They definitely shouldn’t be ashamed. It’s not their fault! But if a parent has this attitude, I think that’s a mistake. ADHD is not a superpower.

ADHD during adolescence has been associated [...] with significant academic, psychosocial, emotional, and cognitive impairment.

(Ibid.)

In general, if you, as a parent, can help your kid avoid something with the word “disorder” in the name, you should probably at least think about it. Some adults love to act all condescending when they see youth glued to their screens or having trouble socializing but the fact is that it’s not the kid’s fault. Do you really expect a 5-year-old kid to get an iPad and to say “no, dad, I will pass on this bright-colored attention-grabbing machine, please hand me a Rubik’s cube instead”?

It’s not just ADHD

ADHD is bad, but it’s far from the only bad thing that stems from modern technology. Kids are exposed to porn, even of the hard-core variety, at a much earlier age than you’d think. They are influenced by content that was optimized for engagement, often to the detriment of its truthfulness and usefulness. They have 24/7 access to an A.I. sycophant that has been known to spur kids to self-harm and share dangerous falsehoods. They are subjected to a rampant new way of bullying — cyberbullying — that can become psychologically even more intense than the good old-fashioned in-person bullying of yesteryear. (In the past, people could only bully you when you were physically near them. Now they can do it 24/7, and coordinate the effort much more efficiently.)

In a 2024 study, researchers found that the new interaction scheme where you swipe through ultra-short auto-playing videos (popularized by TikTok) hinders analytical thinking. Kids literally get dumber. But hey, it also increases engagement and ARPU so tech companies copy the scheme left and right. Because saying no to this design would be bad for shareholder value, see?

Toddlers & tablets

Ok, enough of this. Let’s look at some practical advice.

My first piece of advice is not to buy a tablet for the kid. At least not too early.

Apparently, something like 60% of kids have their own tablet by the time they’re 4 years old.

Now, I am a parent and I totally get why parents do this. It’s so stressful when your kid starts to cry or throws a tantrum, and at that point, you’d do anything to stop it. Not because you’re a lazy parent but because it hurts your soul to see the kid in distress.

At that point, an iPad is like magic. You give it to the kid, and suddenly — calm. The kid watches videos, plays kid-friendly games, and stops crying. What’s more, the videos and the games make it look like the kid is actually learning. “Let’s count to 10,” starts one. “We are shapes!” say a bunch of geometrical figures. A train goes by with colors. “Fantastic,” you think, “these videos are actually good for the kid.”

First of all, they’re not. I don’t believe it matters that your kid can list all the colors a few months earlier than you could when you were young. The videos and games all look educational so that the parents feel good about them, but it’s mostly for show. They never go beyond the most basic knowledge because anything harder kills engagement and ARPU. As a content creator and as a YouTube algorithm, the last thing you want is to bore the kid, or make them think too hard, or — god forbid — get a little frustrated.

And frustration is my point here. Parents of all previous generations did not have iPads or smartphones or any other perpetual attention-grabbing tech devices. If a kid before the 2010s got bored or had a tantrum, it was still very uncomfortable for the parents but there was no easy out. And so the kid had to get it out of the system. And slowly, the kid learned how to deal with things like boredom, anxiety, and frustration.

You’d be surprised how soon toddlers learn that there are situations where they don’t get what they want. And that it’s okay. Bored? Come up with a little game or start humming. Frustrated? Anxious? Sure, get it out of your system but life goes on.

In little steps, a healthy kid can go from a total tantrum jockey to a reasonable toddler in a few weeks. These weeks can be excruciating for the parents but that’s nothing new under the sun. Parents had to endure crying kids since the dawn of humanity.

But put an iPad into the equation and this learning goes out of the window. What parent will say no to something that makes their crying kid happy in the span of a few seconds?

And so the toddler doesn’t learn to deal with even the slightest forms of anxiety and boredom. And since they don’t learn gradually at an early age, they will have a much harder time later. This can lead to the phenomenon known as failure to launch, in which teenage kids cannot deal with the anxiety of leaving their parents and being at school. But that’s just the extreme. There are plenty of kids who go to school just fine but have a little less capacity to endure boredom or anxiety than if they had just been left to their own mind, once in a while, when they were younger.

Now, my point isn’t to make everyone an anti-technology zealot. There’s clearly a sliding scale here. Our kid did watch videos on a tablet once in a while — especially on long, multi-hour road trips, such as when we rode from San Francisco to LA, but oftentimes also at home. But it wasn’t a default. And if I were to go through toddler years again, I’d lean on a tablet as an entertainment/distraction device less, not more.

So again, the best option, in my opinion, is just not to let the toddler use a tablet or a smartphone at all. But if you must, then the other thing I recommend is to load the device with movie files that you actually want the kid to be able to watch. Don’t let the kid browse Netflix or YouTube Kids. Those are optimized for engagement. The algorithm (known as “personalization” in the industry) is tuned to pick content that keeps the user glued to the screen. Which is often the opposite of what you want.

Unfortunately, installing an app like Netflix is so much easier than buying/downloading a video file and putting it on a device. I recommend older shows, which are both better for the kid’s brain development (they’re generally less fast-paced, which is good) and easier to find without DRM. You can probably find torrent files of these older shows, and if all else fails, there’s yt-dlp. (I told you that this stuff requires way too much tech savvy these days, didn't I.)

The show that we loved to watch with the kid is a local one called Little Mole (Krteček). Try to contrast the vibe of that show with something more modern, like Paw Patrol or Blippi.

Mobile phone and elementary school kids

The kid grows and starts spending more time away from their parents. In school. Visiting a friend’s house. At the convenience store buying milk. This is another point at which many parents give in and provide the kid with a smartphone.

When our kid started commuting to and from elementary school by himself, my wife and I were close to that decision, too. The school is well over 30 minutes away by mass transit, and the kid needs to change buses at a busy station. So we thought it would help if he had an online map with GPS.

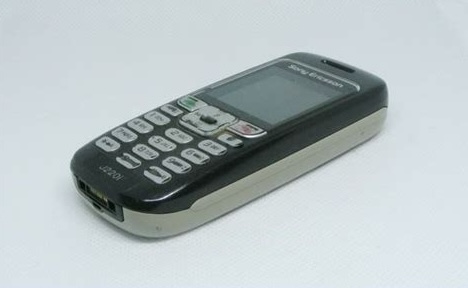

We resisted, and looking back, I’m really glad we did. Instead, we gave the kid my old 2G phone from 2005 — and when that stopped working (it only supported up to 2G networks), we bought a modern feature phone. It can make calls, send old-fashioned SMS text messages, and it has a snake game.

I had to invest some time teaching the kid the route to school. Gradually, I let him lead the way more and more, until one day I just told him that the next day, he’s coming back from school by himself. Now he’s better at using the 1M+ city’s mass transit than most of his peers. We never had any problem — but even if we did, we know he can call us. And he knows that, if push comes to shove, we’ll come pick him up. A feature phone is all you need at this age.

Meanwhile, the kid’s classmates have smartphones. They’re not better at navigating the city, despite having access to online maps, and they fill every moment of downtime watching videos, scrolling feeds and playing “sticky” mobile games.

Problematic Smartphone Use (PSU) is defined by excessive use that is accompanied by daily dysfunction and symptoms similar to behavioral addiction, e.g., loss of control or compulsivity. [...]

[P]revious studies showed associations between PSU and poorer wellbeing/lower quality of life,19,21,22 more behavioral difficulties,19,23,24 poorer peer and family relations,25 and poor academic performance26 in children and adolescents.

You might think our kid suffers because he doesn’t have the latest iPhone. And I know there were times at which he really wished that he had a smartphone just like the others. But he’s doing fine. In fact, quite recently his classmates apparently told him (and the only other kid who doesn’t own a smartphone) that they envy them. The way they put it is that these two feature phone kids “live in the 90s.” And, as I understand it, 1990s are now really cool somehow.

Video games

I’m a gamer and game developer so you might think that I surely give my kid unlimited access to video games. Once again, nothing could be further from the truth.

I have nothing against kids playing games that are “old school hard.” The kid can play snake all day long — but he doesn’t because old school snake is a ruthless game. It doesn’t try to shield you from failure like modern optimized-for-ARPU games do. When you make a mistake in snake, it’s game over. It doesn’t matter how many in-game currencies you have (there are none) or that you were this close to beating the record. There’s no “coyote time” or any other system that tries to subtly help you avoid frustration and failure.

The kid is now a pretty decent player of snake but he’s never glued to the screen for unhealthy amounts of time.

The kid has also been playing Super Mario Wii since about 2nd grade. That game is way more polished than snake, and clearly has some affordances like the aforementioned “coyote time”, but it’s still pretty ruthless compared to modern free-to-play mobile games. It took the kid many days before he could clear the first level, World 1-1. As you can imagine, the sense of achievement was all the stronger.

I don’t know where I read this advice, but if you decide to have a video game console at home, put it in the living room. This works really well for us. The kid associates playing video games with family fun, and there’s no way for him to shut himself away for unhealthy amounts of time while playing. In a living room, you always compete for the space with other members of the family, and you tend to self-regulate your time much better, too.

Personal computing device

Ok, the kid is in elementary school. Sooner or later, they’ll need a personal computing device. Something they can do homework on, possibly something for Zoom calls.

For some reason, many parents go for a smartphone or tablet in this situation. I guess it’s because a these devices are more portable and easier to use? But they’re also much worse at text/precision input, and — in my opinion — they shield the kid too much from some of the useful details of technology.

I have good experience with giving the kid a laptop. Second hand laptops are often cheaper than tablets. I found a Panasonic Toughbook which has the advantage of being really hard to destroy. It’s survived quite a few bumps, and the keyboard is spill-proof. It’s a device meant for use at construction sites where it’s just a matter of time before someone spills their coffee all over the poor thing.

A laptop is, at first, harder to use than a tablet, but once the kid learns to use the trackpad and the keyboard (which is very soon), they have a device more suited for creating than for consuming. I know that there are creative apps on tablets, and that you can attach a keyboard, and that tablet operating systems do allow multi-tasking these days. But laptops still win in the long run, in my opinion. My kid was drawing sprites in PICO-8 in first grade (while having a model open in a separate window) and creating Google Slides comics in third grade. I’m sure there are examples of elementary school kids who are writing novels on their smartphones or whatever — after all, the tech is just one part of the equation — but my point is that you can choose the device that subtly nudges the kid in a useful direction, and a laptop can be one such device.

One downside of laptops is that their operating systems tend to have much worse parental controls than their tablet counterparts. And you do need parental controls. You can’t just let the kid freely browse the internet, or even just YouTube. You also want to set a timer so that the kid learns that the computer is just for a while each day, and then you have to make your own entertainment.

My first pick for an operating system was Linux, of course. But unfortunately, I could find only one stable parental control system on Linux, and it broke constantly. In my testing, it was simply failing to load at startup, or it loaded but didn't have any effect. It was also laughably easy to circumvent. (Maybe not by a 1st grader on their first day with the device, but a bit later? Definitely.)

So, with a heavy heart, I switched to Microsoft Windows. And I have to say that it mostly works. You get a website and a mobile app that you can use to set up the limits, review the kid’s recent activity, and give exceptions when the kid asks for it (like when they need to prolong their computer time that day). The parental system (called Family Safety) is integrated into the OS on a deeper level than the parental control plugin on Linux, so it’s way harder to circumvent it. The “you’re out of time” screen is visibly at the same OS level as the Ctrl-Alt-Delete screen. And no, you can’t Ctrl-Alt-Delete out of it.

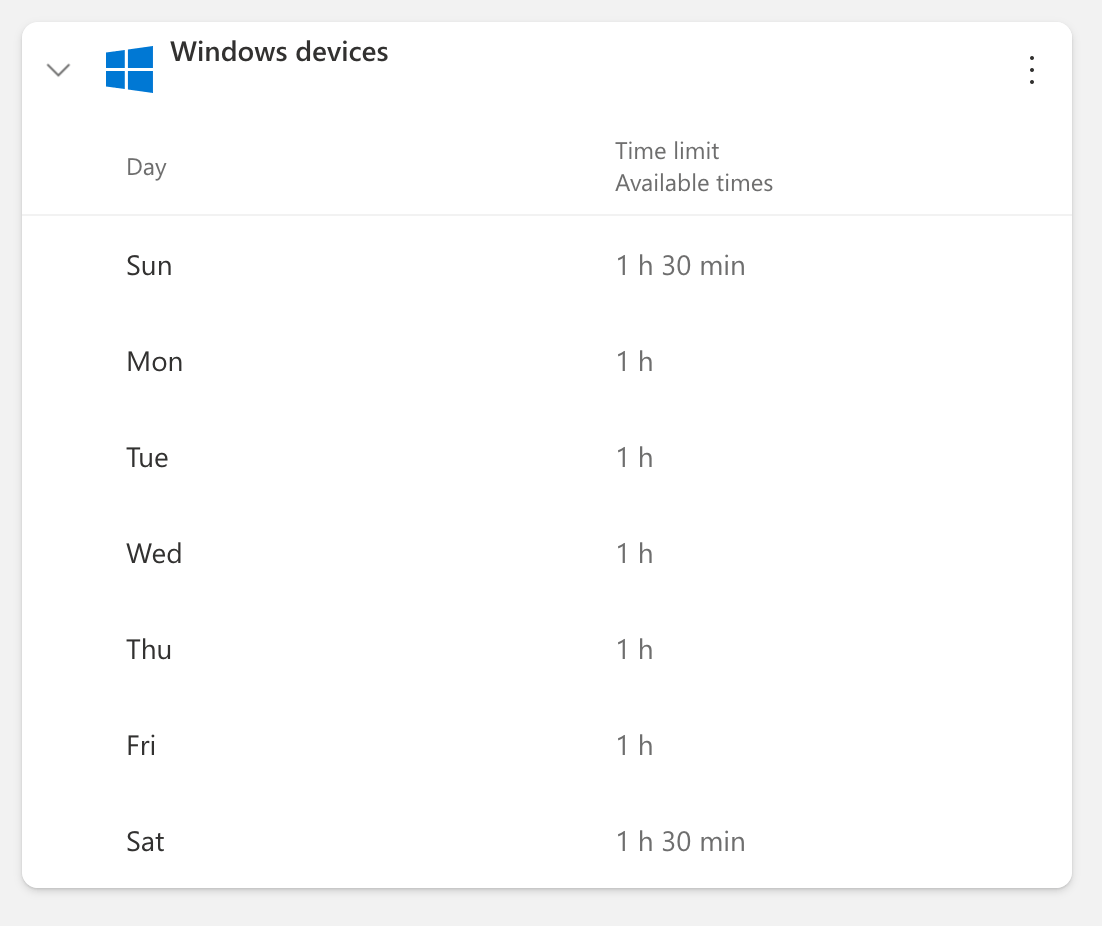

Here’s the way I have Family Safety set up for the kid now. This has worked quite well for us.

- computer use: 1 hour Mon-Fri, 1½ hours Sat-Sun

- you can set times of day which are unavailable, but I just have the whole day, every day

- you can control websites that the kid can visit, but it only works in Microsoft Edge

- so I only have Edge installed on the laptop

- there’s some default filtering (of things like porn) so I left that on

- I also disallowed YouTube (but allowed YouTube Kids)

- you can also set maximum time per app

- internet use (Edge): 15 minutes

- Minecraft: 30 minutes

Earlier, I said that laptops are — at least at first — harder to use than tablets. Not just because of the indirectness of touchpad → cursor (as opposed to the directness of using a touch screen) but also because the operating system has rougher edges. There are confusing menus, overlapping windows, and a very visible file system.

That’s a blessing in disguise, though. This is how you actually get tech skills. Not by using an iPad as a toddler, touching colorful icons and swiping through videos, but by dealing with more complex technology when you’re a bit older. I’m not saying my kid’s now a tech wizard (nor do I want him to be) but he’s leaps and bounds ahead of his classmates. He’s more likely to see tech issues as something understandable and solvable.

Standalone web apps

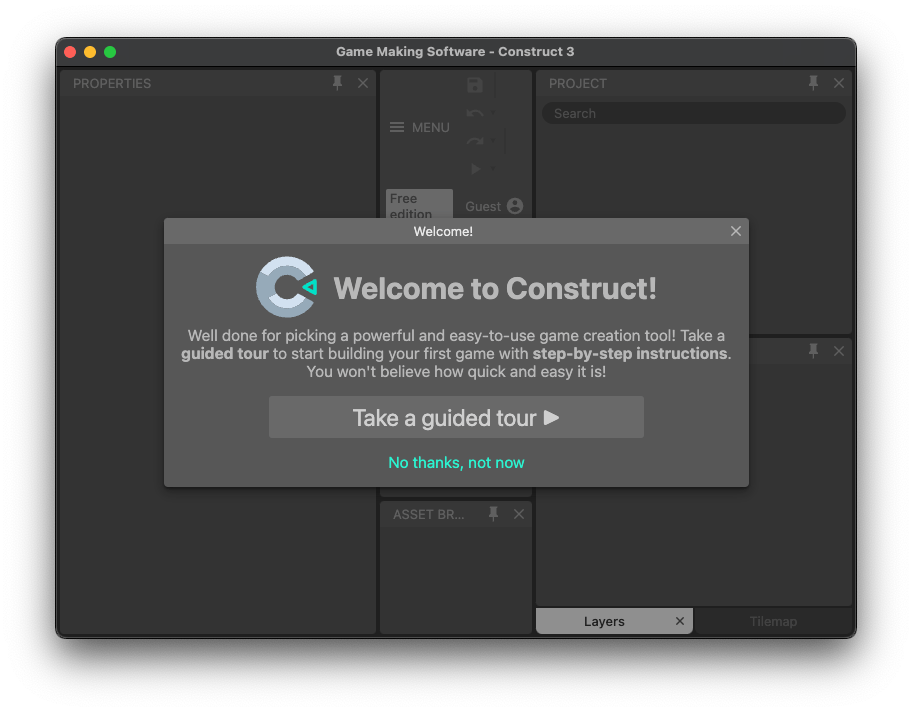

Many useful tools these days are now websites. For example, my kid expressed a desire to make his own platformer video game one day, and at that point the best fit for his ability was Construct 3 — an online game engine. Basically, a web app.

That’s a problem if you want to limit the kid’s use of the internet. Family Safety doesn’t have any mode where you could say “limit internet time but don’t count time spent on Construct 3”. At the time, the kid tended to open Edge, go to YouTube Kids, and spend the entirety of the allotted time (15 minutes) watching videos. Which is not what I wanted the kid to do on the computer. When I temporarily increased the time allotment so the kid would have time for Construct, it went exactly as you’d expect — he just spent the whole time watching videos. Not that he planned to do that, mind you. But watching video after video on YouTube is something that just comes naturally. It’s what the site is designed for, and it’s hard, even for adults, to keep track of time while doing it.

The solution to this problem is to build an app that’s basically a custom browser that opens on a specific web app, and only allows you to access that one web app.

Thankfully, there’s already a system for that. It’s called Electron, and its “hello world” app is literally this. (Maybe without the disallow part.)

So I wrote a little project that opens the Construct 3 website in a window and only allows you to make games, nothing else. I even disallowed browsing the community games list (which is part of the Construct 3 web app) so that the kid wouldn’t have to deal with the temptation of just playing others' little games.

(The screenshot above is from macOS because that’s where I test the app. But obviously the kid gets a Windows version.)

It worked so well that I reused the same project for several other web apps. For example, the Czech Television website for kids is so good that I don’t mind that the kid spends time there. Another web app that I made into a standalone app is one for math training — which I’m pretty sure the kid never opened by himself. Oh well.

In the end, I transformed the project into a factory for such Electron apps. You can find it here on GitHub.

The way I set it up, you write a TOML file like this:

name = “construct3-standalone”

productName = “Construct 3”

version = “1.1.0”

description = “A standalone Construct 3 browser”

author = “Filip Hracek”

[build]

appId = “net.filiph.construct3”

[build.win]

icon = “icons/construct3.ico”

[directories]

buildResources = “build”

[start]

url = “https://editor.construct.net”

[whitelist]

# List of allowed URLs (as regular expressions) that the user can navigate to.

# (They can change the page to such a URL or open a new window with it.)

navigate = [

'editor\.construct\.net',

'preview\.construct\.net',

'account\.construct\.net',

'www\.construct\.net\/en\/make-games\/manuals',

'www\.construct\.net\/tutorials',

'www\.construct\.net\/en\/tutorials',

]

# List of URLs (as regular expressions) that the page can access.

# For example, you might want to allow the site to call APIs

# from play.google.com without allowing the user to navigate

# to that site.

embed = [

'.+\.construct\.net',

'construct-static\.com',

'googleapis\.com',

'ssl\.gstatic\.com',

'fonts\.gstatic\.com',

'googletagmanager\.com',

'play\.google\.com',

]

And then you just run the code with something like standalone --input path/to/your.toml and voilà, you have a standalone app (for Windows, Mac or Linux).

Just to be clear, this is a personal project, provided as is. Everyone’s free to fork and improve on it. It’s MIT-licensed.

The age of AI

My experience with the impact of modern A.I. on kids is limited — the LLM revolution is still young, after all. There is basically no serious research yet and so, as far as I know, we’re a bit in the dark.

My feeling is that kids should probably have some access to LLMs, just to gain experience. It can be fun to sit down with the kid and let them “drive” an AI chat. They’ll ask the LLM to make little poems about farts or whatever, and that’s actually something that LLMs excel at. The kid might have questions about verifiable facts, such as what is the largest planet in the solar system or who is the oldest person alive — and that’s also okay. But I’d personally want to be around when the kid is asking about topics where LLMs tend to hallucinate, and where the hallucination can be dangerous.

A British AI safety NGO lists things like dangerous advice (encouraging self-harm, starvation diets) and misinformation, among other things. You may have heard about the kid who committed suicide after spending time with ChatGPT. The kid’s father said that the chatbot discouraged his son from seeking help and even offered to write his suicide note. Something that a real person probably wouldn’t do.

That’s an extreme example, of course. That said, wherever there are extreme examples, you can probably find less extreme cases, too. For instance, it looks like some of my kid’s classmates got real lazy after getting unchecked access to a chatbot, using it for as much class work as they can get away with. It’s understandable. Why would you go through all the trouble of using your brain and stringing sentences together when you can just ask the computer to do it for you?

So maybe giving kids 24/7 access to an LLM is a mistake. But I feel much less strongly about this one than the stuff above. There’s just not enough experience to pull from.

What else?

I want to reiterate that this is just a single parent’s interpretation of the research available to him. I’m not a pediatric psychologist. I also don’t have access to all the research. For example, there’s this one data analysis study from 2023 which apparently finds that while there is a statistical link between screen time and depression and anxiety, there’s no link with ADHD. But the full text of that study is behind a paywall, and the study stands against several other studies (some of which it cites, just to be clear). Are they talking about ADHD itself (which, as I say above, is mostly genetic, and has little to do with technology use) or are they actually saying that screen time is not worsening its symptoms? Anyway, my money is on the studies that do show a link between screen time and worsening ADHD symptoms — but that’s simply a layman’s opinion.

This is not meant to be a definitive guide. I hope that someone with more expertise can shed light on the best available research and recommend best practices for regular parents.

I just wanted to put something out there. Harmful effects of modern technology on youth seem like (another...) set of potential problems for our collective future, don’t they? And it’s a problem where there’s a lot of hand wringing and pearl clutching but almost no practical advice.

— Filip Hráček

January 2026