Filip Hráček / text /

Videogames that teach you stuff

A successful urban planner recently shared how he got into urban planning because of SimCity, which he played as a kid.

I personally know a pair of very successful startup founders who credit Quake II modding, of all things, for getting them into building products.

When a friend asked a bunch of teachers what they thought was the best educational game, none of them mentioned any games that were actually designed as educational. They instead talked about commercial videogames such as Civilization and Minecraft.

School by Play

My compatriot John Amos Comenius, who lived 350 years ago, is considered the father of modern education. In 1630, he published Škola hrou, in which he complained about lazy, unmotivated students (a phenomenon that somehow seems completely unprecedented to each new generation of parents and teachers) and provided a solution: let the students play the things they should be learning.

_(1592-1670)._Tsjechisch_humanist_en_pedagoog._Als_voorganger_van_de_Moravische_of_Boheemse_Broedergemeente_verdreven_en_sedert_1656_gevestigd_te_Amsterdam_Rijksmuseum_SK-A-2161.jpeg)

In his time, this meant theatrical plays. For example, one of the performances was about the king Ptolemaios, to whom four scholars summarized the entirety of human knowledge. There was no real story or action—the kids were memorizing long monologues in Latin. But hey, this was still a big improvement over the best educational approaches of that day.

Which is weird, because nothing is more natural than learning by play.

Look at kittens

Have you seen kittens play? Aren’t they cute?

Guess what. When you see kittens playfully pounce at yarns and each other, what you’re actually seeing is them training to kill. That’s what play is! In nature, play didn’t evolve as a way to pass time. It evolved as a relatively safe way for younglings to train at their future roles—hunters, parents, leaders, warriors.

Play is great at picking up skills. It’s not that great at learning data points. This is where a lot of confusion and disappointment happens. Sure, you can design gameplay that teaches important historical dates. It can be done. But it’s not ideal. It leads to dull, proficiency-test-like games. It’s not where play-as-learning shines.

Learning patterns

Let’s say we want students to understand, really understand, that there are situations in which a small mistake today can lead to a huge catastrophe later.

Option A is to just tell them. They will hear what you say, and will be able to repeat it on a test later. But it’s unclear if they’ll really understand.

Option B is to give them a concrete example. Maybe a case in which a historical general made a seemingly small mistake that led to a big defeat later. This is better than Option A, because students have a story to come back to, but it’s still not ideal.

Option C is to give them a chessboard and let them play. They will experience making a small mistake that later leads to catastrophe. It’s not just a story now. It’s something that happened to them. If you let them experience it multiple times, they will learn the pattern. They won’t just have the knowledge of this phenomenon, they’ll also have some skill to recognize it and avoid it.

Videogames

Videogames let you experience things that a chessboard or a theatrical play can’t. They’re simulations. You can try running a city, building a civilization, surviving in the wilderness, colonizing a star system, or digging into an ancient mountain.

Some of these simulations are very simplistic and disconnected from reality (think Super Mario or 2048). They’re closer to a chessboard in that they teach you very basic patterns, but very deeply. Play enough Super Mario, and you’re sure to learn the importance of staying calm in the face of pressure, for example.

On the other end of the spectrum, you have games that try to simulate as precisely as possible. A realistic flight simulator (like Microsoft Flight Simulator) will actually teach you quite a lot about airplanes, aerodynamics, and air traffic control. A realistic war game (like Command: Modern Operations) is closer to a military software tool than to a videogame, and can be used by governments and military organizations for training. A realistic business simulator (like Capitalism II) can be used as a teaching tool for economics departments at prestigious universities such as Harvard.

And then there are videogames that try to simulate complex systems in a more or less realistic way, but without sacrificing fun. These are my favorite.

SimCity is not a realistic simulator of urban planning—it completely ignores much of the problem space. But it’s a good balance. It forces you to think about at least some aspects of urbanism while keeping it approachable even to kids. Civilization, similarly, isn’t going to teach you how to become a statesman, but it will let you experience some of the aspects of human history and nation-building in a simplified, enjoyable way. And Minecraft, well, let’s just say that if your only source of survival skills is Minecraft, you shouldn’t go camping in the wilderness just yet. But, is the game fun? Does it give you a safe environment to try things you definitely shouldn’t try in real life? Yes and yes.

So videogames are amazing, right?

Look, videogames have lots of fans. If you’ve read this far, chances are you’re one of them. So am I. It would be convenient, for you and me, to take away from all this that videogames are just the best, and anyone who doesn’t like them is clearly wrong and biased.

But, let’s be honest, videogames have lots of problems. I’m obviously not going to go through all the things in which videogames can be harmful. Suffice to say that we now know, for example, that there is something called “videogame addiction” and that it’s not that rare. We all see that, for some kids, playing videogames almost completely displaces alternative and healthier forms of spending free time.

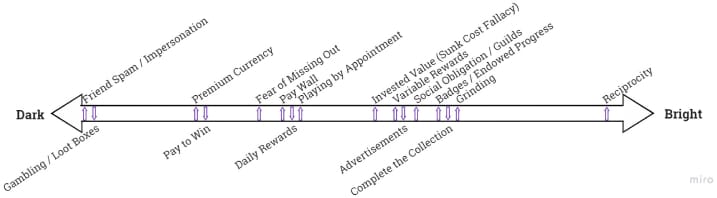

We are also, hopefully, all aware of the ways in which some videogame companies manipulate players through psychological tricks (sometimes called “dark patterns”) to extract as much money or “engagement” from them as possible.

Those are all topics for another time. Here, I’d like to talk specifically about gameplay-as-teaching.

I’d say that you can find teachable moments, learnable patterns in every game. Even the most toxic pay-to-win mobile game will teach you something. If nothing else, the game will teach you yet another UI, which could theoretically make your brain more adaptable to computer interfaces that you’ll see in the future.

But the obvious question is: how much of some type of skill do you really need?

Counter Strike teaches you hand-eye coordination and some basic tactics (coordinate attacks). But how many hours do you put into the game before the increased skill is only really helping you with the game itself? It is, of course, completely fine to play games for recreation. I just want to prevent some overzealous gaming enthusiasts from thinking that all gaming is actually, you know, good for them. That their 500th hour playing Candy Crush is helping them grow as a person. It most definitely doesn’t.

What we need

I think that what we need is a shared understanding of what videogames can teach most effectively. Patterns. Cognitive skills. Understanding. (Not so much pure knowledge, such as who did what when.)

I think the sweet spot for the types of games that teach the most could be described as:

- A sandbox-like game…

- … that lets you experience a simulated environment…

- … which has something important in common with the real world.

The thing that’s in common with the real world can be thematic:

- SimCity—urbanism

- Kerbal Space Program—engineering

- Crusader Kings—medieval politics

- Transport Fever—mass transit

- etc.

Or it can be functional:

- Dwarf Fortress—resource management

- Factorio—logistics

- Portal—spatial reasoning

- Skyrim—personal & reputational growth

- etc.

And, of course, we need to understand that no game can teach you everything. Kerbal Space Program, in itself, will not make you a NASA engineer. If that’s your goal, you need to turn to much less fun (but ultimately more impactful) ways of learning, such as a university degree.

Make games

I think we need more games that consciously teach you stuff without sacrificing fun.

My gamedev debut from 2021, Knights of San Francisco, is a D&D-style romp on the surface, but it’s also designed to train reading comprehension.

My upcoming game, GIANT ROBOT GAME, is once again a romp on the surface. One in which you operate a giant battle robot in a sort of real-time strategy fashion. But when I’m done with it, it’s going to teach basics of some important real-life skills (such as, browse through your own file system and change a text file, don’t be afraid of config files, etc.).

I know there are folks out there who are itching to make videogames. I hope this article persuades some of them to drop the usual suspects (platformer, FPS, shoot ’em up) and instead create a videogame that teaches stuff.

And I hope we all realize how important it is to celebrate videogames that aren’t just designed to kill time, but to provoke thought, inspire creativity, and teach skills — without sacrificing fun.

— Filip Hráček

August 2023